Nutrition et démence chez les personnes âgées

Conférencière : Carol Greenwood, Ph. D., professeure, département des sciences de la nutrition, Université de Toronto; chercheuse titulaire, unité de recherche appliquée Kunin-Lunenfeld, Baycrest Centre, Toronto (Ontario).

La Dre Greenwood a placé le thème de sa discussion sur la nutrition et la démence dans le contexte des considérations sur les influences environnementales constituant un risque de déclin cognitif et de démence. Même si la démence a d’importantes racines génétiques, les facteurs environnementaux jouent un rôle important dans son étiologie. Selon certaines études, ces facteurs sont associés à environ 60 % des cas de démence survenant après l’âge de 80 ans.

Habitudes alimentaires augmentant le risque de déclin cognitif

Pour bien comprendre le risque posé par les facteurs environnementaux, la Dre Greenwood a recommandé à ses auditeurs de porter attention au régime alimentaire sur une longue durée plutôt qu’à des cas particuliers d’apports alimentaires, bons ou mauvais. La connexion entre nutrition et démence repose sur l’idée sous-jacente que les neurones ont besoin d’apports nutritifs. Des changements nutritionnels entraînent des modifications du métabolisme neuronal. Une alimentation saine garantit la signalisation de l’insuline dans le cerveau, nécessaire à l’apprentissage et à la mémoire. Les cliniciens doivent encourager des habitudes alimentaires propres à maintenir les concentrations cérébrales de neurotrophines nécessaires à la plasticité synaptique impliquée dans la consolidation de la mémoire; de plus, une bonne alimentation et des apports nutritifs appropriés peuvent réduire l’inflammation et le stress oxydatif, et maintenir la capacité de la circulation cérébrale à fournir les nutriments essentiels au cerveau.

Des progrès dans ce domaine de recherche permettraient de contrer l‘isolationnisme qui marque parfois la perception des maladies chroniques. Le cerveau est fortement subordonné à la santé de l’organisme tout entier et une modification de l’alimentation peut exercer une influence directe sur des mala- dies liées au régime alimentaire, comme les maladies cardiovasculaires (MCV), le diabète de type 2 et la dépression.

De nombreuses études épidé-miologiques sur l’alimentation sont disponibles et indiquent qu’un apport calorique excessif engendre un stress oxydatif. La Dre Greenwood et ses collègues se sont penchés sur le rôle des apports en graisses. Un apport élevé en graisses, surtout saturées et polyinsaturées, accompagné d’un déficit en graisses oméga, est typique de l’alimentation nord-américaine. Des études ont montré que les régimes alimentaires faibles en fruits, en légumes, en céréales complètes et en huiles de poisson sont associés à un risque plus élevé de démence. Ce régime est également associé aux MCV, au diabète, à la dépression et à d’autres états pathologiques inflammatoires et chroniques. Les effets indésirables sur le cerveau ne sont pas simples, et il est probable que des mécanismes multiples sont impliqués; dissocier le rôle de la maladie chronique d’un impact direct sur la fonction cérébrale risque de donner une fausse idée de ces effets.

Les huiles de poisson constituent un bon exemple de la façon dont un nutriment particulier peut intervenir sur des voies neuronales multiples. Les études portant sur les huiles de poisson et le risque de démence ont eu du mal à isoler le rôle propre de ces huiles parce que, comme tous les nutriments, celles-ci ont de multiples effets sur l’organisme. Comme les graisses oméga font partie des recommandations alimentaires, la distinction entre le rôle soi-disant phy-siologique du nutriment et son rôle pharmacologique s’estompe. L’incorporation de graisses oméga dans un régime alimentaire holistique est une bonne approche, qui « stimule » le système. L’autre approche compte sur un impact pharmacologique important avec une stratégie de type « cibler et isoler » grâce à des suppléments alimentaires et un enrichissement nutritionnel (comme les œufs). Mais une telle approche néglige d’autres propriétés très précieuses des protéines de poisson.

De la même façon, des recherches sur les avantages cliniques associés à une exposition altérée aux antioxydants ont isolé des micronutriments et les ont fournis sous forme de suppléments alimentaires, ce qui a abouti à des données ambiguës. Cependant, on ne peut pas extrapoler les effets de cette consommation à ceux d’un régime alimentaire incorporant des micronutriments sur la base d’un apport nutritif mesuré en grammes par jour. L’approche ciblée oublie également que le cocktail nutritif complet est plus important (p. ex. : aspect synergique) que la consommation de chaque composé séparément. Les constituants alimentaires fonctionnent en bloc.

Il existe des enjeux pressants étant donnés les changements des marqueurs de santé à l’échelle de la population tout entière. Les personnes présentant une adiposité centrale (associée au développement du syndrome métabolique) sont des « bombes à retardement » de comorbidités. Les résultats de nouvelles études indiquent que l’obésité centrale autour de la cinquantaine augmente le risque de démence, indépendamment des comorbidités diabétiques et cardiovasculaires; les sujets présentant le degré le plus important d’obésité centrale triplent leur risque de déclin cognitif1.

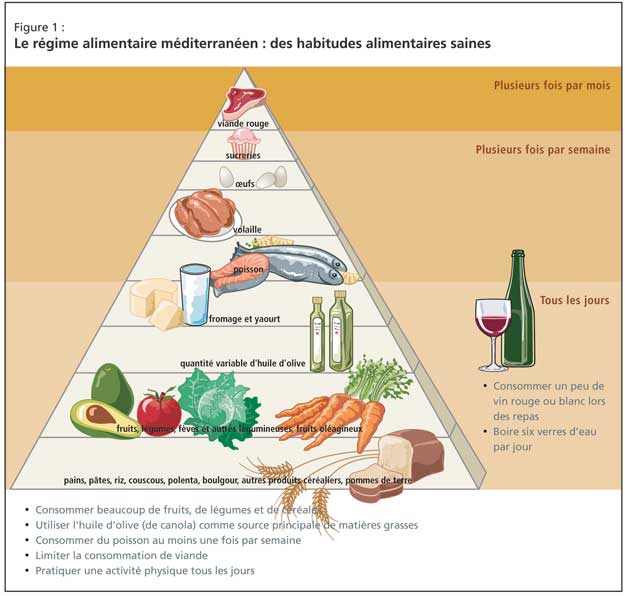

Le régime alimentaire méditerranéen

L’approche clinique de tels patients doit inclure un changement d’habitudes alimentaires, et les données probantes proviennent principalement du régime méditerranéen (Figure 1). Les effets bénéfiques sont directement liés à l’augmentation des apports en fruits, en légumes et en poisson, et à la réduction de la consommation de viande rouge. De récentes données en faveur de cette approche ont été fournies par une étude prospective de 2 258 sujets non atteints de démence en milieu communautaire à New York; mieux le régime méditerranéen était suivi, plus le risque de maladie d’Alzheimer (MA) était faible2.

Le rôle du contrôle glycémique et du diabète de type 2

De plus en plus de données scientifiques laissent entendre que le diabète est en soi un facteur de risque de déclin cognitif, ce qui nécessite un contrôle glycémique draconien chez les patients hyperglycémiques.

Des études animales ont apporté des preuves de l’interrelation entre contrôle glycémique et démence, et la Dre Greenwood et ses collègues ont examiné l’effet des habitudes alimentaires typiquement nord-américaines sur la performance cognitive du rat, particulièrement sur l’apprentissage et la mémoire. Les bais-ses de performance étaient clairement associées à une consommation riche en graisses saturées : les rats soumis à ce régime étaient plus susceptibles d’avoir des performances aléatoires lors des tests.

Il reste à identifier quels aspects du régime riche en graisses saturées nuisent à la fonction cognitive, et à démêler ces effets de ceux du diabète. La Dre Greenwood a mentionné des études présentant les résultats d’une évaluation neuropsychiatrique habituelle de personnes âgées hyperglycémiques, qui examinait plus particulièrement la mémoire immédiate et différée (cette dernière faisant appel à la fonction hippocampique). Les résultats montrent que les personnes les plus insensibles à l’insuline réalisent la moins bonne performance. Avec l’âge, la perte de sensibilité à l’insuline est liée à une détérioration de la mémoire.

Maladie chronique et risque accru de démence

Les recherches actuelles indiquent de plus que la résistance à l’insuline peut excéder les effets de la consommation de graisses sur le déclin cognitif. Des études récentes s’appuyant sur l’imagerie structurelle éclairent la relation entre diabète et cognition. Une étude examinant la perte de la fonction hippocampique chez des sujets âgés non encore diagnostiqués pour un diabète de type 2, mais dont le contrôle glycémique est défaillant, a trouvé qu’un très mauvais contrôle glycémique était fortement associé à une atrophie hippocampique. De tels effets sont évidents chez les personnes dont le diabète est bien maîtrisé; à mesure que le diabète perdure et que les sujets perdent le contrôle métabolique et développent une hyper-cholestérolémie et une hypertension, l’atrophie se propage dans le cerveau et des lésions de la substance blanche se manifestent. Ce sont les composantes vasculaires du diabète, qui apparaissent plus tard au cours de l’évolution de la maladie.

La voie de signalisation de l’insuline est nécessaire à la mémorisation

La Dre Greenwood a fait observer que, bien que le cerveau ne soit généralement pas considéré comme un organe sensible à l’insuline, la densité cérébrale de récepteurs de l’insuline est élevée, et les voies de signalisation de l’insuline jouent un rôle intégral dans la consolidation de la mémoire. Ces voies sont perturbées chez les diabétiques. De telles associations avec les voies de signalisation de l’insuline sont importantes et peuvent expliquer les mauvaises performances de mémoire des personnes diabétiques par rapport à des non-diabétiques d’âge apparié, mais ce n’est pas une preuve irréfutable d’une contribution du diabète à la pathologie de la démence.

La Dre Greenwood a suggéré qu’une perturbation des voies de signalisation de l’insuline contribue sûrement à cette pathologie. L’enzyme de dégradation de l’insuline est l’enzyme clé impliquée dans la dégradation du peptide Ab, qui favorise le développement des plaques de la ma-ladie d’Alzheimer. Cette enzyme est régulée à la baisse dans le cerveau des diabétiques, ce qui ralentit la dégradation du peptide Ab. De plus, de fortes concentrations périphériques d’Ab entravent l’exportation d’Ab, et constituent donc un risque élevé d’accumulation du peptide Ab. Les diabétiques présentent également des niveaux élevés de cytokines inflammatoires, engendrant une accumulation pathologique du peptide Ab et des réponses inflammatoires correspondantes. La cascade inflammatoire du peptide Ab favorise la formation de plaques.

Des études portant sur des sujets au diabète bien maîtrisé, mais porteurs d’un polymorphisme génétique au niveau du gène codant pour le facteur de nécrose des tumeurs (TNFa), corroborent cette idée. Ces individus sont moins à même de fabriquer le TNFa et de déclencher des réponses inflammatoires. Les porteurs de SNP (polymorphisme nucléotidique) obtenaient de meilleurs résultats aux tests et leur baisse de performance était moindre. Le rôle des cytokines inflammatoires en terrain diabétique fait selon toute vraisemblance partie intégrante de l’entretien de la santé cérébrale, a déclaré la Dre Greenwood.

Des perturbations de la voie de signali-sation de l’insuline peuvent également contribuer à la formation des enchevêtrements neurofibrillaires. En particulier, le taux de GSK-3, une enzyme atténuée par la voie de signalisation de l’insuline, peut augmenter chez les diabétiques. La GSK-3 est importante, car elle augmente la phosphorylation de la protéine tau associée à la formation des enchevêtrements neurofibrillaires, et ces derniers sont plus nombreux en terrain diabétique ou obèse. L’accumulation d’enchevêtrements signale le passage d’une perte normale de fonction à une pathologie. En conséquence, certains ont avancé que la MA est la séquelle cérébrale du diabète, ce que réfute la Dre Greenwood, bien qu’elle pense que la maladie se manifeste plus rapidement dans ce contexte.

Habitudes alimentaires favorisant le bien-être cognitif

La principale recommandation alimentaire au patient diabétique doit être de consommer des aliments à faible indice glycémique. Les études portant sur la performance cognitive postprandiale ont constaté que les fonctions de mémorisation et de remémoration étaient altérées après une consommation d’aliments à glucides simples. Il semble que ce soit la sécrétion de cortisol induite par l’insuline, et non les modifications de la glycémie, qui est la clé de cette réponse. L’augmentation du cortisol entraîne des effets problématiques sur l’hippocampe, dont certains sont liés au stress oxydatif. En outre, les diabétiques bénéficiant d’un bon apport en antioxydants souffrent de baisses cognitives moindres. La clé réside dans un contrôle glycémique minutieux afin de minimiser l’agression diabétique répétée au cours de la journée.

Conclusion

La Dre Greenwood a fait observer que les modifications du régime alimentaire des personnes âgées peuvent s’interpréter comme une recommandation de perte de poids, et ce risque est souvent avancé comme objection aux modifications alimentaires. Aucune ligne directrice claire ne permet au médecin de décider quand cesser d’encourager la perte de poids, qui est corrélée à un risque de fragilité chez la personne âgée. La meilleure approche pour minimiser la fragilité, a-t-elle conseillé, c’est d’améliorer les apports nutritifs tout en faisant plus d’exercice physique. Une approche plus ferme des habitudes alimentaires est nécessaire, étant donné que l’incidence du diabète et du syndrome métabolique évolue, notamment en raison du vieillissement de la génération du baby-boom. La Dre Greenwood a averti son auditoire que les forces contribuant à l’augmentation de la démence sont largement sous-estimées, et qu’il est grand temps d’instaurer des modifications du mode de vie.

Bibliographie

- Whitmer RA, Gustafson DR, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Central obesity and increased risk of dementia three decades later. Neurology 2008;71:1057-64.

- Scarmeas N, Stern Y, Tang MX, et al. Mediterranean diet and risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 2006;59:912-21.