Click here to view the entire report from the 28th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Canadian Geriatrics Society

Nutrition and Dementia among Older Adults

Speaker: Carol Greenwood, PhD, Professor, Department of Nutritional Sciences, University of Toronto; Senior Scientist, Kunin-Lunenfeld Applied Research Unit, Baycrest Centre, Toronto, ON.

Dr. Carol Greenwood contextualized her discussion’s theme of nutrition and dementia as contributing to considerations of the environmental influences posing risk for cognitive decline and dementia. While dementia has important genetic roots, a large causative factor is environmental exposure. In cases of disease onset at >80 years of age, studies have suggested that ~60% relates to this factor.

Dietary Patterns that Increase Risk of Cognitive Decline

To understand the risk mediated by environmental exposure, she recommended that listeners focus on chronic diet rather than on instances of good or poor intake. The connection between nutrition and dementia relates to the underlying idea that neurons require nutritional support; altered nutrition equates to altered neuronal metabolism. Sound nutrition maintains brain insulin signaling, needed for learning and memory. Clinicians should aim to promote dietary habits that maintain brain neurotrophin levels, which support synaptic plasticity needed for memory consolidation; further, good diet and appropriate nutrient intake can reduce inflammation and oxidative damage, and maintain the cerebrovasculature’s capacity to supply essential nutrients to the brain.

Advances in this area of research could help to remediate an isolationist philosophy that can pervade viewpoints on chronic disease. The brain is highly sensitive to the health of the body, and through dietary modification it is possible to exert direct impact on diet-associated conditions such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes, and depression.

Many epidemiologic studies on diet are available, indicating that excess caloric intake leads to oxidative stress. Dr. Greenwood and colleagues have examined the role of fat intake. High fat intake, particularly of saturated and polyunsaturated fats, along with a dearth of Omega fats, are typical of the North American diet. Studies have shown that diets low in fruits, vegetables, whole cereal grains, and low in fish oils are associated with higher risk of dementia. This diet profile also associates with CVD, diabetes, depression, and other inflammatory and chronic disease states. The adverse effects on the brain are not simple, and multiple mechanisms are likely involved; separating the role of chronic disease from a direct impact on brain function would distort the effects.

Fish oils exemplify how individual nutrients can modulate multiple neuronal pathways. Studies involving fish oils and dementia risk have found the individual role hard to isolate because they, as all nutrients, have multiple effects in the body. As the Omega fats are incorporated into dietary recommendations the so-called physiologic role of the nutrient versus the pharmacologic role blurs. Incorporating the Omega fats on a wholistic nutritional basis is the sound approach, one that “nudges” the system. The other seeks to exert a large pharmacological impact with a “targeting and isolating” approach through supplements or food enrichment (e.g., eggs). Such an approach overlooks other aspects of fish protein that are valuable.

Similarly, investigations of health outcomes associated with altered antioxidant exposure have isolated micronutrients and supplied them in supplemental form, producing equivocal data. However, measuring the effects of this consumption should not be extrapolated to the effects of a dietary pattern that incorporates micronutrients on a grams per day nutritional intake. The targeted approach also overlooks that the full nutritional cocktail is more important (e.g., the synergistic aspect) than consuming any one individual compound. Food constituents work together.

These are pressing issues given the population-wide changes in health markers. Individuals with central adiposity (associated with development of the metabolic syndrome) are a “time bomb” of comorbidities, she stated. New study results suggest that central obesity in midlife increases dementia risk independent of diabetes and cardiovascular comorbidities; individuals with the greatest degree of central obesity bear a threefold increase of cognitive decline.1

The Mediterranean Diet

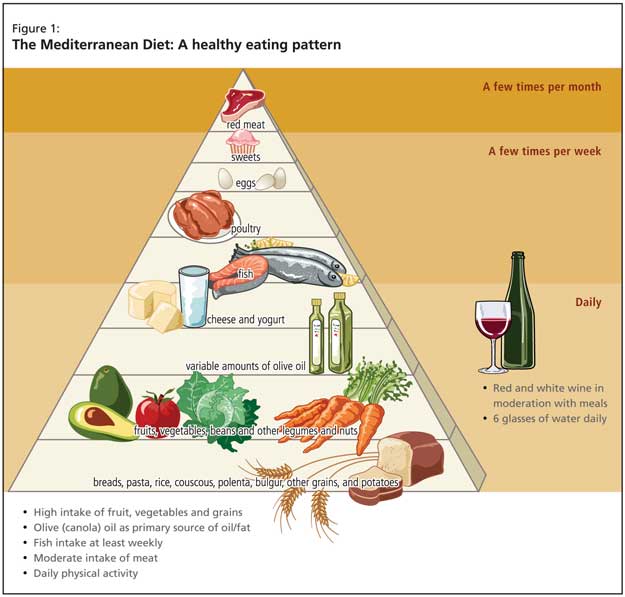

The needed clinical approach for such patients supports changing eating patterns, and the burden of evidence points toward the Mediterranean diet (Figure 1). The beneficial effects relate directly to increased fruit, vegetable and fish intake and reduced red meat consumption. Recent evidence for the approach was provided by a prospective study of 2,258 community-based nondemented individuals in New York; those with higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet had lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD).2

The Role of Type 2 Diabetes and Glycemic Control

Increasing evidence suggests that diabetes per se appears to be a risk factor for cognitive decline, necessitating aggressive glycemic control in hyperglycemic patients.

Evidence for the interrelationship of glycemic control and dementing illness has been drawn from animal studies, and Dr. Greenwood and colleagues have investigated the effect of typical North American dietary patterns on cognitive performance in rats, specifically on learning and memory. Performance decrements were clearly associated with high saturated fat consumption; rats fed this diet were most likely to show random/chance performance in testing.

The task is to identify which qualities of the high saturated fat diet compromise cognitive function, and to disentangle these effects from diabetes’ effects. Dr. Greenwood cited studies with standard neuropsychiatric assessment results of hyperglycemic older adults, looking specifically at immediate and delayed recall (the latter calls on hippocampal function). Results show those more insensitive to insulin exhibit worse performance. With age, lost insulin sensitivity relates to impaired memory function.

Chronic Disease and Enhanced Dementia Risk

Current research further suggests that insulin resistance may outweigh the effects of fat consumption on cognitive decline. Recent studies using structural imaging have cast light on the relationship between diabetes and cognition. One study investigating loss of hippocampal function in older individuals not yet diagnostic of type 2 diabetes but with compromised glucose control found that worse control strongly associated with hippocampal atrophy. Such effects are evident among well-controlled diabetic individuals; as diabetes endures, and individuals lose metabolic control and develop hypercholesterolemia and hypertension, atrophy disperses throughout the brain, and the presence of white matter lesions becomes evident. These are the vascular components of diabetes appearing later in its course.

Insulin Signaling Is Needed for Memory Processing

Dr. Greenwood observed that while the brain is not often considered an insulin-sensitive organ, it has a high density of insulin receptors, and insulin signaling pathways play an integral role in memory consolidation. These insulin signaling pathways become disrupted in the setting of diabetes. These associations with the insulin pathway are important and may explain why the diabetic individual has poor memory performance relative to an age-matched nondiabetic, but it is not clear indication that diabetes contributes to dementia pathology.

It likely does both, Dr. Greenwood argued. The key enzyme involved in degradation of Ab protein promoting development of AD plaques is the insulin degrading enzyme, which is down-regulated in the brains of those with diabetes, slowing Ab degradation. In addition, the Ab export is impaired due to high levels of Ab in the periphery, leaving them at high risk of Ab accumulation. Diabetics also have higher levels of inflammatory cytokines, producing a disease state of Ab accumulation and corresponding inflammatory responses. The Ab inflammatory cycle facilitates plaque formation.

Studies featuring individuals with well-controlled diabetes but carrying a genetic polymorphism to tumour necrosis factor (TNF)a support this view. Such individuals are less able to manufacture TNFa and launch inflammatory responses. Those carrying the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) have performed better on testing and showed fewer decrements in performance. The role of inflammatory cytokines in the context of diabetes is likely integral to the maintenance of brain health, Dr. Greenwood stated.

Disturbances to the insulin signaling pathway may also contribute to the development of neurofibrillary tangles. Specifically, GSK-3, an enzyme dampened by the insulin signaling pathway, may be increased in those with diabetes. GSK-3 is important because it increases phosphorylation of the tau protein associated with development of neurofibrillary tangles, which appear in greater levels in the diabetic/obese state. The accumulation of tangles signals the move from normal loss of function into pathology. Correspondingly, some have argued that AD is the brain sequelae of diabetes, and while Dr. Greenwood expressed her disagreement, she thinks the disease occurs more rapidly in this setting.

Dietary Patterns that Promote Cognitive Well-Being

The focus of dietary recommendations for the diabetic patient should be on low-glycemic index food intake. Studies that have investigated postprandial cognitive performance found that after consuming simple carbohydrate foods, degraded processing and recall function results. It appears that insulin-induced cortisol secretion, and not changes in blood glucose, are key to this response. Increased cortisol exerts problematic effects in the hippocampus, some of which relate to oxidative stress. Further, diabetic individuals with sound antioxidant intake experience fewer decrements in cognition. The key is careful glycemic control to minimize the diabetic insult occurring repeatedly throughout the day.

Conclusion

Dr. Greenwood observed that the risk of appearing to recommend weight loss to an older population is often raised as an objection to dietary modification. There are no clear guidelines as to when physicians should stop encouraging weight loss, which is correlated with frailty risk with advancing age. The best approach to minimizing frailty, she advised, is improved nutritional intake combined with increased exercise. A more aggressive approach to dietary patterns is required, given that the incidence of diabetes and the metabolic syndrome are changing, especially as baby boomers age. Dr. Greenwood advised listeners that the pressures driving dementia upward are vastly underestimated, and now is the time to implement lifestyle modifications.

References

- Whitmer RA, Gustafson DR, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Central obesity and increased risk of dementia three decades later. Neurology 2008;71:1057-64.

- Scarmeas N, Stern Y, Tang MX, et al. Mediterranean diet and risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 2006;59:912-21.