Une amélioration de la qualité des projets qui soit réussie et publiable

Conférencier : Roger Wong, BMSc., M.D., FRCPC, FACP, Département de médecine, Université de Colombie-Britannique, Vancouver, BC.

Le Dr Roger Wong a animé une discussion pratique et un atelier pour des étudiants en gériatrie sur l’amélioration de la qualité des projets. L’amélioration de la qualité est un domaine de compétence professionnelle associé au rôle de gestionnaire du gériatre, l’un des sept rôles définis par CanMEDS. Le cadre CanMEDS a été créé par le Collège royal des médecins et chirurgiens du Canada en tant que ressource pour la formation médicale, les compétences du médecin et la qualité des soins, qui visent toutes à satisfaire aux besoins de la société en matière de santé.

L’amélioration de la qualité (AmQ) est une compétence centrale du gériatre, a expliqué le Dr Wong, et elle est essentielle aux objectifs de devenir un meilleur médecin et d’offrir de meilleurs soins aux personnes âgées. Le Dr Wong s’est appliqué à donner une vue d’ensemble de l’AmQ.

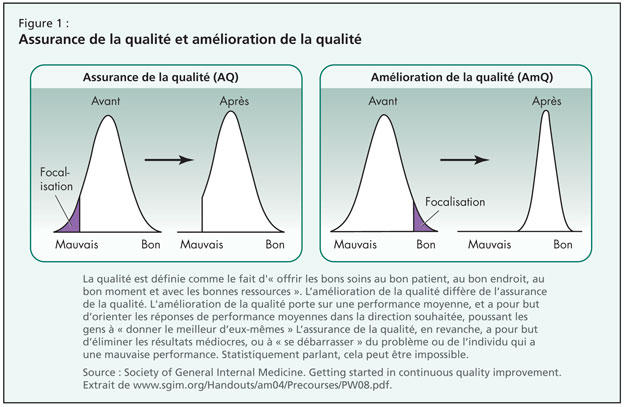

Il a défini la qualité comme le fait d’« offrir les bons soins au bon patient, au bon endroit, au bon moment et avec les bonnes ressources ». L’amélioration de la qualité diffère de l’assurance de la qua-lité par l’accent qu’elle met sur le déplacement complet de la courbe de résultats vers un but explicitement défini, un but qui est atteint grâce à un modèle d’amélioration intentionnellement programmé et exécuté (Figure 1). Plutôt que de viser l’élimination des résultats médiocres, la mise en œuvre de l’AmQ se concentre sur la performance moyenne et vise à bâtir sur la réussite fonctionnelle, en identifiant ce qui marche dans une organisation et en permettant à ses membres de fonctionner à leur meilleur.

Comme cadre permettant l’amélioration, le Dr Wong a présenté une approche pour améliorer la performance organisationnelle grâce au modèle PDSA (plan, do, study, act), c’est-à-dire « planifier, faire, étudier, agir ». Planifier a pour objet de fixer des buts ; faire définit des mesures réalisables ; étudier s’intéresse à cibler des domaines de changement ; et agir représente la mise en œuvre et l’évaluation des changements.

Le Dr Wong a alors abordé les attri-buts d’une équipe d’AmQ efficace. Une telle équipe a besoin de leadership ayant l’autorité ou l’influence pour amener le changement ; elle requiert que les membres de l’équipe aient une compétence clinique, et comprennent le problème à résoudre et les principes de l’AmQ ; et elle choisit au jour le jour des meneurs capables de diriger le cours du projet d’AmQ.

Il a ensuite proposé un travail dirigé sur l’établissement de buts, définis par des objectifs clairs, concis et adaptés à la population ; il est important de noter que cette phase de l’AmQ s’attache à définir un résultat mesurable—un résultat qui s’étend au-delà du statu quo tout en restant raisonnable dans le contexte—à atteindre en un temps imparti. De bons buts s’efforcent d’assurer que les participants ressentent que les buts sont significatifs et mesurables, de façon à ce qu’ils ne commencent pas à rejeter leur adhésion au programme d’AmQ. Il a mis en garde contre le fait que des objectifs trop ambitieux nécessitent une remise au point et un travail préalable sur une portion plus réduite du système. Un but intéressant en contexte gériatrique pourrait être la détermination d’une valeur cible particulière pour la glycémie de patients participant à un programme de traitement du diabète (p. ex., « Au cours des 12 prochains mois, 80 % de nos patients diabétiques auront des taux confirmés d’hémoglobine A1c de 7 % »).

Une fois un but significatif déterminé, l’établissement de graphiques met l’accent sur les étapes d’un processus. Le fait de suivre de façon précise un problème aide à repérer des zones qui pourraient être négligées en tant que zones d’amélioration potentielles. Le graphique, a-t-il insisté, doit se concen-trer sur un processus clinique, et non pas sur le système complet de soins médicaux ; éviter de trop entrer dans les détails ; intégrer toutes les principales étapes du processus clinique en cours ; et rendre compte du processus tel qu’il se produit en réalité. L’établissement de graphiques a pour objectif de rechercher des zones d’erreur, de transitions, de conflit, de confusion, de délai ou de pro-blèmes au sein du processus. Il devrait y avoir des mesures multiples, notamment du résultat (comment le système a-t-il fonctionné ?), du processus (les portions ou les étapes du système ont-elles fonctionné comme prévu ?) et des mesures de stabilisation (des changements conçus pour améliorer une portion du système causent-ils des problèmes ailleurs ? P. ex., la réduction du séjour à l’hôpital donne-t-elle lieu à des taux de réadmission plus élevés ?).

Remarquant que toute amélioration requiert un changement, le Dr Wong a rappelé à son auditoire que la méthode « PDSA » est une façon de tester si les changements mis en place ont effectivement apporté des améliorations.

La deuxième phase de la communication du Dr Wong a porté sur la présentation des outils d’amélioration. Il a examiné comment établir un organigramme du projet, dans lequel les buts d’amélioration de la performance peuvent être présentés par un diagramme qui suit les objectifs, les buts, les échéances, le leadership et le soutien nécessaire.

Le Dr Wong a alors abordé l’échantillonnage (la collecte de données) pour le « PDSA » et a distingué entre l’échantillonnage systématique, qui recueille les données à des moments fixes ou à intervalles définis et qui est utile dans les processus à fort volume, et l’échantillonnage par blocs, qui consiste à sélectionner des échantillons dans des blocs de taille prédéfinie pour produire des données en fonction du temps. De tels projets supposent de déterminer la quantité de données à collecter ainsi que la façon de les présenter. Il a mis en garde sur le fait que les données présentées sous forme d’agrégats peuvent obscurcir la variation des données au cours du temps et faus-ser ainsi le jugement sur les stratégies d’AmQ. Pour l’évaluation des données, il a insisté sur la distinction entre une variation de cause commune (interne au système ; reproductible ; affectée de façon aléatoire) et une variation de cause spéciale (inhabituelle et attribuable aux circonstances). Le plan d’action approprié sera dicté par le type de variation.

La dernière partie de l’atelier a porté sur l’orientation pour identifier des domaines de projets intéressants en médecine, surtout ceux qui ont un impact sur les soins gériatriques. Les bons projets d’AmQ peuvent mettre en jeu des interventions visant à réduire les erreurs, gérer le temps, évaluer les pertes ou améliorer les interactions clinicien-patient. Les projets d’équipe en gériatrie peuvent porter sur des transitions de médication (p. ex., le passage de la mo-xifloxacine de la voie IV à la voie orale) ou favoriser la continuité des soins (p. ex., en étudiant les effets des télécopies d’information envoyées aux médecins de famille après hospitalisation). Il a encou-ragé les étudiants à réfléchir à des domaines d’amélioration dans leur contexte local et, avant de conclure, il a engagé les participants de l’atelier à faire l’exercice d’imaginer un projet d’AmQ et de produire une proposition d’objectif.

Pour la planification des projets d’équipe, il a recommandé de porter une attention particulière à l’ampleur du projet. Les chefs de projet doivent s’assurer que le projet est d’une ampleur gérable, que les participants sont préparés à faire face à des résultats négatifs, qu’un temps adéquat est alloué aux activités d’AmQ, que des capacités de communication sont mises en jeu, que les parties prenantes sont intégrées au projet, et qu’un suivi longitudinal est mis en place pour s’assurer que les membres de l’équipe sont sur la bonne voie. Le Dr Wong a rappelé à son auditoire qu’il existe des lignes directrices communément acceptées pour la publication de projets d’AmQ (p. ex., les lignes directrices baptisées SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence), en ligne au www.squire-statement.org).