Systems Approach to Fracture Prevention: The Ontario Project

Speaker: Earl Bogoch, MD, FRCSC, University of Toronto; St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, ON.

Dr. Earl Bogoch’s key message concerned the importance of identifying and treating osteoporosis after a fragility fracture, in order to prevent future fractures, most importantly of the hip.

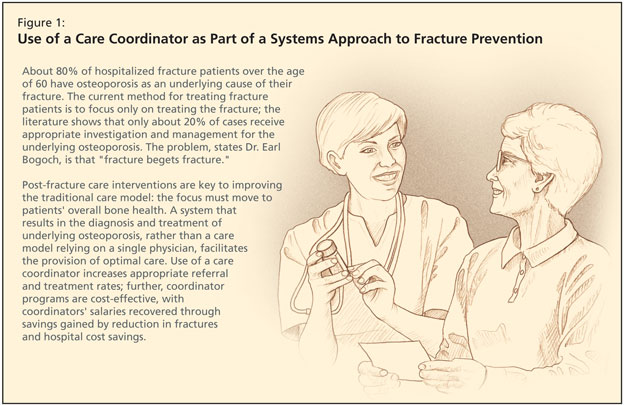

The care gap for patients after a fragility fracture is well-known and exists internationally. This problem is significant; about 80% of hospitalized fracture patients over the age of 60 have osteoporosis as an underlying cause of their fracture. From the age of 50, half of women and one-fifth of men are likely to experience an osteoporotic fracture. The economic burden has been well documented as well as major personal morbidity—and mortality—in those with hip fractures, with loss of function and independence.

The current method for treating fragility fracture patients may focus only on treating the fracture; the literature shows that only about 20% of cases receive appropriate investigation and management for the underlying osteoporosis.

Dr. Bogoch offered a critique of the traditional care model that relies on the expertise and initiative of a single doctor, which serves osteoporosis care poorly. While surgeons deal with fractures, frequently no one focuses on patients’ bone health. The solution he posed is a system that results in the diagnosis and treatment, rather than a care model relying on a single physician.

Ten years ago, Dr. Bogoch carried out a study in five Ontario hospitals. Patients with wrist, shoulder, vertebral, or hip fractures were provided with a written explanation of the risks of osteoporosis, and a letter was mailed to the family doctor recommending osteoporosis follow-up. Afterward, less than two-thirds saw their family doctor and, of those, 69% had densitometry. Treatment rate went up only slightly, from 17% (historical controls) to 24%. Disappointed with the results, Dr. Bogoch determined that simply informing patients and physicians was insufficient; they needed a coordinator to promote good care.

Other studies in Ontario had similar results; densitometry and treatment rates increased minimally or not at all. The lack of success with these programs led to their decision to focus on the coordinator program (Figure 1).

In this program, coordinators screened all orthopedic inpatients as well as outpatients in their fracture clinic, who had low-trauma fractures of the wrist, hip, vertebrae, and humerus. Coordinators assessed the etiology of the osteoporosis and the patient’s fracture risk. They gave patients recommendations, provided educational materials, communicated with their family physicians, and then closely followed every patient.

Three messages were delivered to fragility fracture patients: 1) Your fracture is probably related to underlying weakness of the bone. 2) By having this fracture, you are now at risk of a hip fracture. 3) Treatment is convenient, safe, and effective.

After 1 year, they found that 95% of their patients received appropriate osteoporosis attention. At 6 months and at 1 year, three-quarters of the patients had undergone a BMD as recommended. Three-quarters of those referred to a specialist had attended, and at 1 year, 50% were adherent with medications. Dr. Bogoch noted that more recent data showed closer to 85% adherence.

According to Dr. Bogoch, similar coordinator or fracture liaison service studies have shown a comparable increase in treatment rates. Further, working with a health economist, they found that the coordinator program was cost-effective, with the coordinator’s salary more than recovered. Additionally, in their cohort of 500 patients, predicted hip fractures were reduced, with considerable hospital cost savings.

There were also other benefits to working with a coordinator: orthopedic surgeons were more likely to document information about overall fragility rather than only the fracture; there was an increase in identification of atypical osteoporosis; there was an improvement in patient knowledge and attitudes; and there was an increase in appropriate referrals to osteoporosis specialists.

A commitment for a comprehensive osteoporosis strategy has now been made in Ontario, and $5 million in annual funding has been committed for this project. The program now includes most types of low-trauma fracture, since they now know they are all predictors of a future hip fracture. Nineteen coordinators work in 33 fracture clinics across Ontario.

They began screening patients in early 2007 and results of the first year were reported. The coordinator met with more than 26,000 patients, about 13,000 of whom completed baseline information questionnaires. They educated 12,000 patients and had an intervention with their family doctor; over 10,000 patients were told they should discuss a BMD with their family physician; and 8,700 family doctors received a letter recommending osteoporosis follow-up. These patients will be followed, and their data linked to CIHI and Ontario Health data, for future fracture rates as well as their utilization of osteoporosis medications, in the over-65 group.

Victoria Elliot-Gibson, osteoporosis coordinator at St. Michael’s and program consultant for Osteoporosis Canada, was the original coordinator of the program, and she addressed the symposium. She explained that osteoporosis screening coordinators are hired by Osteoporosis Canada.

All centres follow a protocol to provide uniformity of care. They screen via a variety of methods because coordinators do not have similar access across all sites, using electronic records, paper charts, or ER referrals. The assessment for each patient is done in a private area. Coordinators are also now collecting consent forms so they can use this data for research purposes. Coordinators have a network, with a website, www.OSCnet.ca. It features a forum for questions to Ms. Elliot-Gibson, as well as relevant articles so that coordinators can stay current with the literature.