Click here to view the entire report from the 28th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Canadian Geriatrics Society

Telomeres, Telomerase and Aging

Speaker: Chantal Autexier, Ph.D., Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, Jewish General Hospital, and Bloomfield Center for Research in Aging; Departments of Anatomy and Cell Biology, and Medicine, McGill University, Montreal QC.

Dr. Chantal Autexier discussed the role of telomeres in the maintenance of genetic and cellular integrity, and how telomere disruption is involved in cellular senescence and the aging process.

Telomeres and Their Role in Cellular Integrity

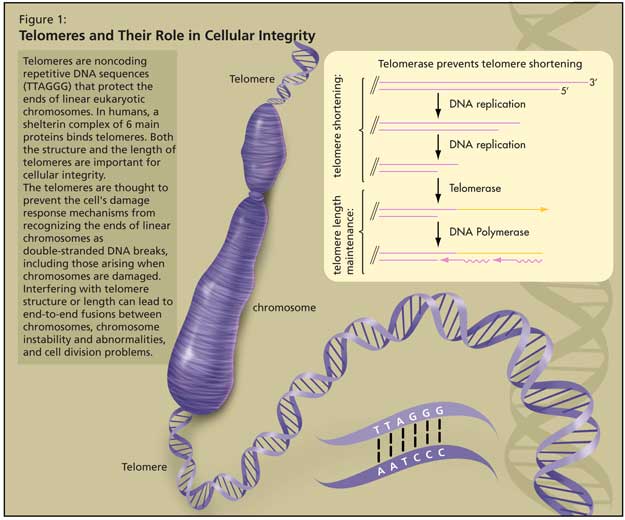

Telomeres are noncoding repetitive DNA sequences (TTAGGG) that protect the ends of linear eukaryotic chromosomes. In humans, a shelterin complex of 6 main proteins binds telomeres.1 Both the structure and the length of telomeres are important for cellular integrity (Figure 1).

The telomeres are thought to prevent the cell’s damage response mechanisms from recognizing the ends of linear chromosomes as double-stranded DNA breaks, including those arising when chromosomes are damaged by stresses such as ionizing radiation. Interfering with telomere structure or length can lead to end-to-end fusions between chromosomes, chromosome instability and abnormalities, and cell division problems (cell senescence, cell death, or cells becoming cancerous).

In the body, most cells are unable to maintain telomere length from one division to the next, as the DNA replication machinery is unable to fully replicate the ends of chromosomes, leading to telomere shortening every time cells divide. Once a critical point—the Hayflick limit—is reached, most cells exit the cell cycle and undergo cell senescence. However, a small proportion of cells are able to re-enter the cell cycle, and this is usually associated with the lengthening of telomeres and the expression of telomerase, an enzyme directly involved in telomere formation and maintenance. Bodnar et al. have shown that forced expression of telomerase prevents telomere loss and growth arrest of normal human fibroblasts in culture and is sufficient for telomere lengthening and cell immortalization (extended lifespan).2

While most cells do not express telomerase, some cells do, such as stem cells, cells of the germ line, and 85% of cancer cells. Such cells are therefore able to maintain telomere length and structure through a large number of cell division cycles.

Telomere Shortening, Cell Senescence, and Tissue Aging

The process by which a cell exits the cell cycle is called replicative senescence. This can be triggered by various stresses, such as radiation damage and oxidative stress.3,4 In many cases, senescence is caused by, or associated with, loss of telomere integrity.

The cell cycle is controlled by multiple checkpoint mechanisms that sense DNA damage, activate repair mechanisms, and trigger cell death when damage cannot be repaired. Tumour suppressors are important cell cycle regulators that regulate cell senescence and death, ensuring that a cell with extensive damage dies or stops dividing. When these checkpoint proteins are absent or malfunctioning, damaged cells continue to grow. Although tumour suppressors protect an organism from the accumulation of damaged cells, they also contribute to tissue aging. As damaged and senescent cells are eliminated through cell death, cell pools responsible for tissue renewal and the maintenance of tissue function are depleted.

In humans and other organisms, tissues that undergo rapid self-renewal—lining of the gut, skin, hair follicles, and bone marrow—are the ones most affected by telomere shortening, cell senescence and cell death. Many age-related pathologies affect these tissues.

According to Dr. Autexier, many studies have shown a correlation between telomere shortening and replicative senescence, cell death and aging, and between telomere length maintenance, the presence of telomerase activity and cellular immortalization, longevity or cancer formation.

Telomere Disruption in Aging

Dr. Autexier explained that many characteristics of natural aging in humans are related to a decline in processes that require continuous cell renewal, or to defective safeguard mechanisms that prevent the occurrence and survival of cells with genomic abnormalities. These include declines in immune and bone marrow functions, skin thickness changes, reduced wound healing capacity, structural changes in epithelial tissues, loss of fertility, and increased incidence of cancer. Research now suggests that loss of telomere integrity is one of the key mechanisms that drive the aging and age-related pathologies.

Dr. Autexier described that premature human aging syndromes, such as Ataxia Telangiectasia, Werner Syndrome, and Dyskeratosis congenita (DKC), share phenotypic similarities with the normal aging process, such as cataracts, osteoporosis, hair graying, and neurodegeneration.5 These syndromes are associated with defects in genes implicated in the maintenance of genomic and telomeric integrity.

DKC phenotypes first present in tissues that undergo constant cell renewal, such as the gut, the epidermis, and the bone marrow.6,7 Patient populations with the autosomal dominant form of the disease demonstrate shorter telomeres, earlier disease onset and more severe symptoms with each successive generation. These results are consistent with a defective telomere maintenance process.

Various forms of DKC indeed arise from mutations in genes that are directly involved in maintaining telomere integrity. So far, DKC mutations have been identified in telomerase, in a component of the telomerase complex called hTR (human Telomerase RNA) and in the gene encoding Dyskerin, a protein that binds to hTR.8,9

The relationship between defective telomerase activity and the aging process was confirmed in the mTR knockout mouse model. Although these mice are viable, successive generations exhibit progressive shortening of telomeres and decreased fertility (the 6th generation being infertile).10 Interestingly, these mice also present reduced wound healing, hair loss and graying, reduced body weight, intestinal villi atrophy, bone marrow failure, and an increased incidence of cancer.11,12

Most phenotypes observed in this mouse model are similar to those seen in DKC patients and, to a certain extent, to age-related pathologies associated with normal human aging.13

Conclusion

Dr. Autexier closed by observing that there have been numerous studies in the last 4 years correlating telomere length and mortality, Alzheimer’s disease status, and longevity. Although these studies are generally correlative, it is interesting to see that more research is being done to look at telomere length as a marker for some diseases associated with aging.14,15,16

Telomere integrity is a key regulator of human aging and cancer formation, suggesting that proteins involved in telomere maintenance could represent molecular targets for therapeutic interventions in the fields of cancer and other age-related diseases.

References

-

Blasco MA. Telomere length, stem cells and aging. Nat Chem Biol 2007;3:640-9.

-

Bodnar AG, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, et al., Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science 1998;279:349-52.

-

Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell 2005;120:513-22.

-

Ithana K, Campisi J, Dimri GP. Mechanisms of cellular senescence in human and mouse cells. Biogerontol 2004;5:1-10.

-

Hasty P, Campisi J, Hoeijmakers J, et al. Aging and genome maintenance: lessons from the mouse? Science 2003;299:1355-9.

-

Kirwan M, Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita: a genetic disorder of many faces. Clin Genet 2008;73:103-12.

-

Marciniak R, Guarente L. Human genetics. Testing telomerase. Nature 2001;413:370-3.

-

Mitchell JR, Wood E, Collins K. A telomerase component is defective in the human disease dyskeratosis congenital. Nature 1999;402:551-5.

-

Dokal I, Vulliamy T. Dyskeratosis congenita: its link to telomerase and aplastic anaemia. Blood Rev 2003;17:217-25.

-

Blasco MA, Lee HW, Hande MP, et al. Telomere shortening and tumor formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell 1997;91:25-34.

-

Rudolph KL, Chang S, Lee HW, et al. Longevity, stress response, and cancer in aging telomerase-deficient mice. Cell 1999;96:701-12.

-

Lee HW, Blasco MA, Gottlieb GJ, et al. Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs. Nature 1998;392:569-74.

-

Marciniak RA, Johnson FB, Guarente L. Dyskeratosis congenita, telomeres and human ageing. Trends Genet 2000;16:193-5.

-

Cawthon RM, Smith, KR, O’Brian E, et al. Association between telomere length in blood and mortality in people aged 60 years or older. Lancet 2003;361:393-5.

-

Panossian LA, Porter VR, Valenzuela HF, et al. Telomere shortening in T cells correlates with Alzheimer’s disease status. Neurobiol Aging 2003;24:77-84.

-

Nakamura K, Takubo K, Izumiyama-Shimomura N, et al. Telomeric DNA length in cerebral gray and white matter is associated with longevity in individuals aged 70 years or older. Experimental Gerontology 2007;42:944-50.