Apathy in Dementia Is a Significant Behavioural Challenge

Speaker: Tiffany Chow, MD, Clinician-Scientist, Rotman Research Institute; Assistant Professor, University of Toronto, Neurology & Geriatric Psychiatry, Toronto, ON.

Dr. Tiffany Chow began with expressing her appreciation, as a neurologist, for her colleagues in geriatrics, whom she honoured for promoting a more holistic approach to patients with dementia, and stressed the importance of working together.

She identified fundamental aspects of quality of life for people with dementia: being pain-free; safe; able to participate in meaningful activities; and able to maintain the greatest degree of autonomy possible. Dr. Chow also described contributors to quality of life for caregivers: emotional connection; the ability to aid the patient (e.g., in feeding); having good downtime together; and the knowledge that everything that can be done is being done.

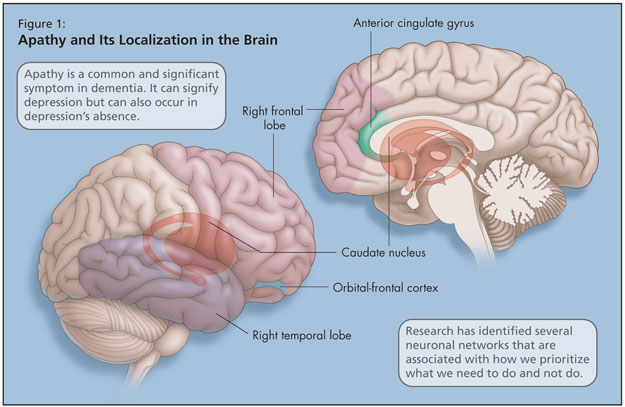

Dr. Chow cautioned against the effects of apathy in patients with dementia, which can impact all dimensions of life quality described above. Apathy is a common and significant symptom in dementia. While apathy can signify depression, it can also occur in depression’s absence, and each can worsen the other. Apathy can keep patients with dementia from being physically motivated to participate in everyday activities and, due to lack of stimulation, this state can hasten cognitive decline.1 Apathy also intensifies caregiver distress and thwarts emotional connection to the patient. It also diminishes treatment compliance (pharmacological or other, e.g., recreational therapy). Apathy may contribute to institutionalization; studies have found lower rates of apathy among community-dwelling patients.

Dr. Chow explained that there are several neuronal networks that manage how we prioritize what we need to do and not do, and they have attempted to localize apathy in the brain (Figure 1). Research into apathy has identified its association with the right temporal lobe, right frontal lobe, caudate, anterior cingulate gyrus (or superior medial frontal cortex), and the orbital-frontal cortex.2

In their recent study,3 Dr. Chow and her colleagues set out to localize clusters of apathy symptoms empirically, with actual patients with dementia, to see whether the affective, behavioural, or cognitive apathy symptoms tended to occur together or in isolation, and whether apathy typically co-occurs with other types of behavioural disturbances.

Dr. Chow showed combined data from Baycrest, Sunnybrook [Health Sciences Centre], UC San Francisco, and UCLA, showing results on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). On the section of the NPI that deals with apathy, patients are questioned on spontaneous activity, spontaneity in conversation, participation in former activities, participation in former chores, demonstration of interest in others, investment in friends and family, and degree of affection.

Results showed that, for those with either FTD or Dementia of Alzheimer’s type (DAT), the most common type of apathy, when present, was a decrease in spontaneous activity. Comparing the percentage of apathy in the two types of dementia, more of the patients with FTD (72%) had apathy than those with DAT (56%).

They also demonstrated all the types of apathy: affective apathy (emotional blunting); behavioural apathy (lack of spontaneous activation); and cognitive apathy (lack of interest in engaging in new cognitive activity). Many patients had all three types, and almost all had at least two. This was true for both types of dementia.

They looked for an association between apathy and other non-apathy variables on the NPI, including impulsivity, separation anxiety, and resistant behaviour, and found that those with the affective type of apathy were much more likely to experience these symptoms than those with other types of apathy or no apathy.

She discussed the results of a study by Robert et al.4 that showed that apathy could be a predictive factor for which patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) will convert to DAT.

There are two groups, one in North America and one in Europe, who are working to get apathy added to the DSM-V (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). The criteria would be lack of motivation (relative to baseline), lack of goal-directed activity (cognitive apathy), lack of interests or goals, and diminished emotional responses (emotional blunting).

Treatment for apathy should be considered on the basis of type of apathy.1,5 For those with affective apathy, an antidepressant might be in order. For behavioural apathy, psychostimulants might be used. For cognitive apathy, cholinesterase inhibitors have shown efficacy. Psychostimulants such as methylphenidate have been shown to be effective and well-tolerated; while dextroamphetamine is in the same drug class, there is only sufficient evidence supporting use of the former. Antidepressants and dopaminergic agents have also been used.

Dr. Chow has looked at whether some of these drugs, for example antipsychotics or other sedatives, might cause apathy in dementia. She and her colleagues investigated this in a cross-sectional study on 69 patients with FTD. Of the four most commonly used medications in this group—nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (probably for arthritic pain symptoms), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, cholinesterase inhibitors, and antipsychotics—none was found to contribute to a higher risk of apathy.

For those interested in learning more on the subject of apathy, Dr. Chow recommended articles by Robert et al., 20096 and van Reekum et al., 2005.1

References:

-

van Reekum R, Stuss DT, and Ostrander L. Apathy: why care? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005;17:7–19.

-

Mendez J, Lauterbach EC, and Sampson, SM. An evidence-based review of the psychopathology of frontotemporal dementia: a report of the ANPA Committee on Research. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2008;20:130–49.

-

Chow TW, Binns MA, Cummings JL, et al. Apathy symptom profile and behavioural associations in frontotemporal dementia vs. Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 2009;In press.

-

Robert PH, Berr C, Volteau M, et al. Importance of lack of interest in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Am J Geri Psych 2008;16:770–6.

-

Malloy PF and Boyle PA. Apathy and its treatment in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Psychiatric Times 2005;XXII(13).

-

Robert P, Onyike CU, Leentjens AF, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease and other neuropsychiatric disorders. European Psychiatry 2009;24:98–104.