Click here to view the entire report from the 28th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Canadian Geriatrics Society

Whole-body Protein Metabolism with Normal and Frail Aging

Speaker: Dr. José A. Morais, MD, FRCPC, Division of Geriatric Medicine & McGill Nutrition and Food Science Centre, McGill University, Montreal, QC.

Aging is associated with changes that may affect body protein metabolism. Dr. José Morais reviewed protein metabolism with respect to studies comparing older and younger adults.

Loss of muscle and its function is the definition of sarcopenia. At any given moment, the amount of muscle mass depends on rates of protein synthesis and breakdown. A mismatch promotes a gain or loss in lean body composition.

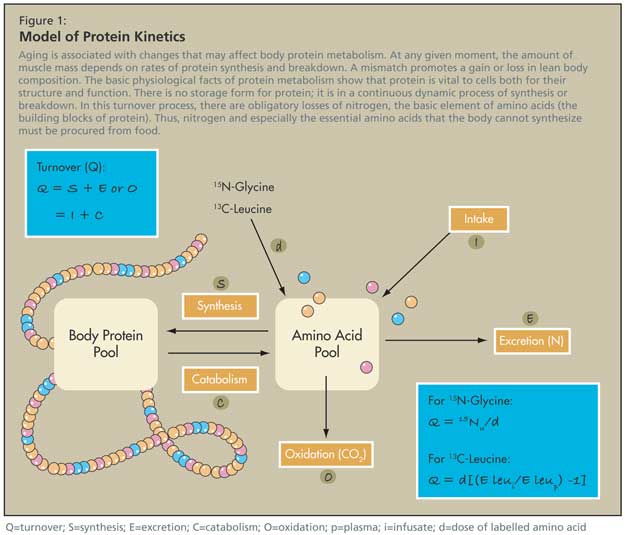

The basic physiological facts of protein metabolism show that protein is vital to cells both for their structure and function. There is no storage form for protein; it is in a continuous dynamic process of synthesis or breakdown. In this turnover process, there are obligatory losses of nitrogen, the basic element of amino acids (the building blocks of protein). Thus, food must compensate nitrogen loss and especially provide the essential amino acids that the body cannot synthesize (Figure 1).

Dose-responses normally exist, meaning that protein intake vs. body protein balance depends on energy intake and quality of protein (reflecting the amount of essential amino acids). The quality of the protein and the amount of intake required are also interdependent.

However, these relationships change during the life cycle. This subject is poorly understood, especially in disease states.

Model of Protein Kinetics

There are ways of measuring the turnover of proteins (protein kinetics) using stable isotope methods. A hypothetical pool of amino acids is in equilibrium with the larger pool of body proteins. Amino acids enter this pool from food intake or protein breakdown from the body, and leave the pool for protein synthesis, or are degraded. The degraded component can be captured in expired air.

In healthy, independent older adults, BMI may be in a normal range (23-25 BMI) but with age, the body shows increased adiposity and decreased lean tissue. Previous studies of protein kinetics show that older persons have lower protein turnover than younger people per kg of body weight. However, Dr. Morais’s observations showed that rates of protein turnover are unchanged with aging when expressed per kg of lean body mass, but this does not preclude changes at the muscle level.

To assess the effect of age on protein turnover rates in the whole body, Dr. Morais and colleagues compared total body MRI scans of young and older subjects, and examined scans of the mid-thigh and abdomen.1 Results showed that the amount of fat infiltration was much greater in the older group, particularly for those with midabdominal adiposity.

In a subgroup of patients tested, they found less lean tissue and muscle in the older subjects. Twenty-four-hour urine excretions were performed to measure muscle protein breakdown—estimated from 3-methylhistidine—as an index of muscle catabolism. Results showed that muscle’s contribution to whole-body protein catabolism was significantly reduced in older persons (25.8% vs. 38.4%; P < 0.001). All measurements were adjusted for lean body mass (LBM).

Dr. Morais concluded that the lower rates of protein kinetics per kg of body weight in older adults are due to lean tissue loss. Further, he found a reduced muscle contribution to whole-body protein catabolism in older persons, due to lower muscle mass and slower fractional catabolism. Older adults’ muscles are less active and experience further health and strength decrements due to dietary protein restrictions. Further, he emphasized that protein is needed in stress states (at a higher intake than recommended) to rebound from conditions such as infection and trauma.

Dr. Morais observed that some emerging data are discordant. A study by Short K et al. on postabsorptive whole-body protein kinetics compared a program of aerobic exercise to a resistance program in terms of its effect on body composition.2 Results of this study showed that aging is associated with a significant decline in protein turnover and a progressive decline in the body's remodeling processes. However, exercise was associated with increased muscle protein synthesis and performance, irrespective of age. Mixed muscle protein synthesis increased 22% (p <0.05) for older and younger test subjects.

Frailty

In his research on older adults, Dr. Morais observed that significant muscle atrophy is associated with frailty. A study of whole-body protein kinetics and muscle protein breakdown compared 8 frail versus 8 healthy older women subjected to an isoenergetic, isonitrogenous diet for 9 days.3 At the end of the diet period, they tested the effects of protein supplementation in frail subjects raised to match protein intake of the healthy group without a concomitant increase in energy.

The protein-enriched diet resulted in an increase in net endogenous protein balance and a positive nitrogen balance at the end of the diet period.

Dr. Morais stated that the higher muscle protein catabolism associated with frailty may represent an accommodation mechanism through which muscle provides amino acids to maintain visceral mass and function, essential for survival, at the expense of muscle mass. In the study, frail women maintained the capacity to retain nitrogen when given higher protein intakes. Such a diet could convey health benefits if sustained long enough to result in lean tissue accretion.

Insulin Sensitivity and Aging

Dr. Morais addressed protein metabolism resistance. Protein synthesis is regulated by insulin (which has its own receptor in muscle cells): in the fasting state, it reduces rates of protein breakdown, while in the postprandial state, it stimulates protein synthesis as long as there is enough substrate for synthesis. A deficiency or resistance to insulin’s action leads to a negative net protein balance, protein loss, and sarcopenia.

However, evidence that age is associated with insulin resistance is discordant. A study that examined the relationship between insulin action and aging using hyperglycemic clamp experiments4 found that age per se is not a significant cause of insulin resistance. In the whole study group, insulin action declined slightly with age but when adjusted for BMI this relationship was no longer statistically significant. A significant BMI-adjusted decrease in insulin action with age was present only in lean (BMI <25 kg/m2) women, in whom percentage fat mass also increased with age (by 0.38% body weight per decade; p = 0.0007).

Other studies support the hypothesis that an age-associated decline in mitochondrial function contributes to insulin resistance in older adults. Dr. Morais discussed a study by Petersen KF et al. that matched young and older subjects for body composition, and tried to eliminate the adiposity factor.5 The researchers found that aging was associated with accumulation of fat in muscle and liver tissues due to a decline of mitochondrial function and altered oxidative and phosphorylative activity.

Muscle Protein Anabolism and the Effects of Insulin

A study by Volpi et al. that measured muscle protein synthesis, breakdown, and amino acid transport found that muscle protein anabolism was stimulated by oral amino acids and glucose in older and younger subjects, though the latter increased their rates of protein retention higher than the older comparators.6 Dr. Morais attributed such a benefit in the young to the effects of insulin.

Dr. Morais and colleagues tested the hypothesis that hyperinsulinemia stimulates protein synthesis when postabsorptive plasma amino acid (AA) concentrations are maintained.7 Subjects were healthy younger and older adults (all older adults had good ADLs and all age groups had a BMI of 22-26 and a nitrogen balance). Infusion rates of glucose were higher in younger versus older participants. Younger participants also had higher rates of protein turnover and synthesis measurements. Protein breakdown was equally supressed in both groups.

Both reduction in absolute fat-free mass and increased adiposity are associated with an altered anabolic action of insulin. Therefore, adiposity is more important to insulin resistance than age alone, and the whole-body anabolic response to hyperinsulinemia decreased with aging, and in women vs. men. This blunted response in older subjects was mediated by insulin’s failure to stimulate protein synthesis. Since amino acids are able to stimulate protein synthesis, older adults might benefit from an increased dietary protein intake to compensate for the insulin resistance of aging.

Conclusion

Dr. Morais concluded that sarcopenia is due in part to aging. Mitochondrial DNA damage leads to decreased function and energy production, and to a reduced capacity of muscle protein synthesis. If mitochondrial function is decreased, energy cannot be used normally and will accumulate, leading to muscle fat infiltration, a recognized cause of insulin resistance. The decrease in muscle protein synthesis itself will lead to sarcopenia, but is aggravated by malnutrition.

Once sarcopenia is present, there is less energy expenditure, which leads to adiposity, and ultimately insulin resistance. The latter can also be exacerbated by inactivity. These factors contribute to a metabolic explanation of sarcopenia of aging.

References

-

Morais JA, Ross R, Gougeon R, et al. Distribution of protein turnover changes with age in humans as assessed by whole-body magnetic resonance image analysis to quantify tissue volumes. J Nutr 2000;130:784-91.

-

Short KR, Vittone JL, Bigelow ML, et al. Age and aerobic exercise training effects on whole body and muscle protein metabolism Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2004;286:E92-101.

-

Chevalier S, Gougeon R, Nayar K, et al. Frailty amplifies the effects of aging on protein metabolism: role of protein intake. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78:422-9.

-

Ferrannini E, Vichi S, Beck-Nielsen H, et al. Insulin action and age. Diabetes 1996;45:947-53.

-

Petersen KF, Befroy D, Dufour S, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the elderly: possible role in insulin resistance. Science 2003;300:1140-2.

-

Volpi E, Mittendorfer B, Wolf SE, et al. Oral amino acids stimulate muscle protein anabolism in the elderly despite higher first-pass splanchnic extraction. Am J Physiol 1999;277(3 Pt 1):E513-20.

-

Chevalier S, Gougeon R, Choong N, et al. Influence of adiposity in the blunted whole-body protein anabolic response to insulin with aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006;61:156-64.