Le rôle du mécanisme RANK/RANKL/OPG dans la perte osseuse : nouvelles perspectives

Viser le ligand RANK augmente la densité minérale osseuse chez les femmes ménopausées : résultats d’essais de phase 3

Conférencière : Alexandra Papaioannou, M.D., M.Sc., FRCPC, Professeure, Directrice du département de médecine, Université McMaster, Gériatre, Hamilton Health Sciences Centre, Hamilton, ON.

La Dre Alexandra Papaioannou a passé en revue les résultats d’essais de phase 3 sur le dénosumab qu’elle a décrit comme un « nouveau produit passionnant » qui fait l’objet de recherches. Tel que l’a expliqué le Dr Robert Josse, le dénosumab est un anticorps monoclonal (IgG2) entièrement humain qui se lie avec haute affinité et spécificité au ligand RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B) (RANKL) humain. RANKL est un médiateur essentiel de l’activité des ostéoclastes.1-3 La Dre Papaioannou a noté que les essais cli-niques n’ont jusqu’ici pas découvert d’anticorps neutralisants1,3 et que les effets du dénosumab sur la résorption osseuse semblent être réversibles.3

Le dénosumab qui réduit les marqueurs du renouvellement des cellules osseuses est administré par injection sous-cutanée tous les 6 mois, ce qui est avantageux chez une population plus âgée. Il a une demi-vie de ~25 à 46 jours.4

La Dre Papaioannou a passé en revue quatre études de phase 3 sur le dénosumab en présence d’ostéopénie ou d’ostéoporose postménopausique.

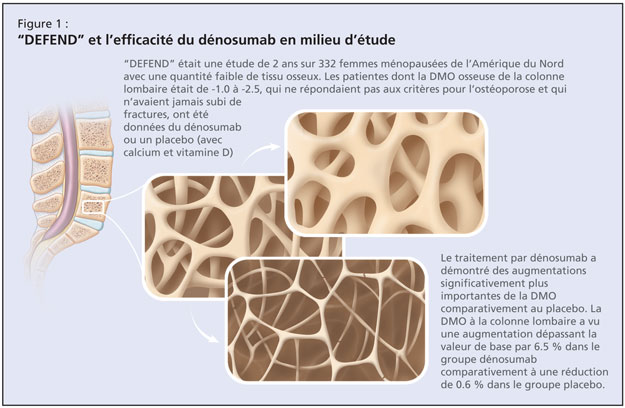

L’étude DEFEND était une étude randomisée à double insu, contrôlée par placebo qui visait à déterminer si un traitement par dénosumab pourrait prévenir la perte osseuse de la colonne lombaire chez les femmes ménopausées souffrant d’ostéopénie (Figure 1).4

Cette étude de 2 ans sur 332 femmes ménopausées de l’Amérique du Nord chez lesquelles la quantité de tissu osseux était faible a étudié les effets du dénosumab ou d’un placébo chez les patientes dont la densité minérale osseuse (DMO) à la colonne lombaire était de –1.0 à –2.5, qui ne répondaient pas aux critères pour l’ostéoporose et qui n’avaient jamais subi de fractures. L’âge moyen était de 58 ans, ce qui constitue une population plutôt jeune, comme l’a noté la Dre Papaioannou. La valeur de base moyenne du score-T de la DMO à la colonne lombaire des participantes était de –1.61. Les patientes ont reçu par randomisation, soit 60 mg de dénosumab, soit un placebo pendant une période de 2 ans. Toutes les patientes ont reçu chaque jour, ≥1000 mg de calcium et ≥400 UI de vitamine D. Le paramètre primaire était la variation en pourcentage de la DMO à la colonne lombaire à 24 mois. Les résultats publiés ont démontré qu’un traitement par dénosumab entraîne des augmentations de la DMO significativement plus importantes pour tous les endroits mesurés, comparativement au placebo (P < 0.05; 95 % intervalle de confiance [IC]). La DMO à la colonne lombaire a vu une augmentation dépassant la valeur de base par 6.5 % dans le groupe dénosumab, comparativement à une baisse de 0.6 % dans le groupe placebo. Des effets secondaires se sont produits dans chaque groupe, les plus communs étant l’arthralgie, la rhinopharyngite et les maux de dos. Il y avait une légère tendance de sérieux évènements indésirables dans le groupe dénosumab.

L’étude DECIDE était une étude randomisée à double insu, comparative avec traitement de référence, qui a évalué les effets du dénosumab comparativement à l’alendronate sur la variation en pourcen-tage de la DMO à la hanche totale à 12 mois, sur 1189 femmes ménopausées.5 Ceci était une étude de non-infériorité sur des femmes ménopausées (≥ 12 mois) avec une faible quantité de tissu osseux et un score-T ≤ –2.0 à la colonne lombaire et à la hanche totale. L’âge moyen des participantes était de 64 ans; ~24 % avaient préalablement reçu une thérapie médicale pour l’ostéoporose et jusqu’à 50 % avaient déjà subi une fracture. Les patientes ont reçu par randomisation des injections de dénosumab (60 mg tous les 6 mois) en plus d’un placebo oral chaque semaine ou de l’alendronate orale chaque semaine (70 mg) en plus d’injections sous-cutanées du placebo tous les 6 mois. Le paramètre primaire était un changement de la DMO à la hanche totale après une période de 1 an. Les résultats publiés ont démontré qu’un traitement par dénosumab entraîne des augmentations significativement plus importantes du changement en pourcentage à partir de la valeur de base de la DMO pour tous les endroits du squelette mesurés, comparativement à l’alendronate. Des augmentations statistiquement significatives de la DMO à la hanche totale ont été observées chez le groupe dénosumab comparativement à ceux traités par alendronate (3.5 % vs 2.5 %; P < 0.0001). Le taux d’abandon était semblable pour chaque groupe et la fréquence et le type d’évènements indési-rables et de sérieux évènements indésirables étaient comparables.

La Dre Papaioannou a ensuite exposé les détails de l’étude STAND, une étude de phase 3 randomisée à double insu, comparative avec traitement de référence, sur des femmes préalablement traitées par alendronate.6 Elle a décrit cette étude comme étant d’une utilité particulière étant donné la fréquence du scénario du patient suivant un régime d’alendronate qui cherche à changer de traitement. L’étude a évalué les effets d’une transition au dénosumab sur les changements de la DMO et des marqueurs biochimiques du renouvellement des cellules osseuses, et sur la sécurité et la tolérabilité, comparativement à la continuation d’un traitement par alendronate. Les participantes étaient des femmes ménopausées (âge moyen de 68 ans) avec une DMO faible, préalablement traitées avec 70 mg d’alendronate une fois par semaine ou l’équivalent pour ≥6 mois. Leurs mesures de la DMO corres-pondaient à un score-T ≤ –2.0 et ≥ –4.0 à la hanche totale. Les patientes ont reçu par randomisation des injections de dénosumab (60 mg tous les 6 mois) ou de l’alendronate orale (70 mg). Le paramètre primaire était la variation en pourcentage à partir de la valeur de base de la DMO à la hanche totale à 12 mois. Les auteurs ont signalé que la DMO à la hanche totale a vu au douzième mois, une augmentation de 1.90 % à partir de la valeur de base, chez des sujets faisant la transition au dénosumab, comparativement à une augmentation de 1.05 % à partir de la valeur de base chez des sujets continuant la thérapie par alendronate (P < 0.0001). Les évènements indésirables, les sérieux événements indésirables d’infections et les néoplasmes étaient comparables entre les deux groupes expérimentaux.

Finalement, la Dre Papaioannou a exposé les détails de l’étude FREEDOM, une étude randomisée à double insu, contrôlée par placebo qui visait à déterminer si un traitement par dénosumab réduit le nombre de femmes ménopausées qui souffrent de nouvelles fractures vertébrales.7 L’étude en cours comporte 7868 femmes ménopausées (-4.0 < DMO score-T < –2.5) âgées de 60 à 90 ans et exclue les individus avec de sévères fractures ou celles plus nombreuses que deux. Les patientes reçoivent par randomisation des injections de dénosumab (60 mg tous les 6 mois) ou un placebo. Les paramètres primaires comprennent la fréquence de nouvelles fractures vertébrales en plus du profil de sécurité et de tolérabilité du dénosumab.

Références :

-

Bekker PJ, Holloway DL, Rasmussen AS, et al. A single-dose placebo-controlled study of AMG 162, a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANKL, in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 2004;19:1059–1066.

-

Elliott R, Kostenuik P, Chen C, et al. Denosumab is a selective inhibitor of human receptor activator of NF-Kb ligand (RANKL) that blocks osteoclast formation and function. Osteoporos Int 2007;18:S54. Abstract P149.

-

McClung MR, et al. Denosumab in post-menopausal women with low bone mineral density. New Engl J Med 2006;354:821–31.

-

Bone HG, Bolognese MA, Yuen CK, et al. Effects of denosumab on bone mineral density and bone turnover in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:2149–57.

-

Brown JP, Prince RL, Deal C, et al. Comparison of the effect of denosumab and alendronate on BMD and biochemical markers of bone turnover in postmenopausal women with low bone mass: a randomized, blinded, phase 3 trial. J Bone Miner Res 2009;24:153–61.

-

Kendler DL, Benhamou CL, Brown JP et al. Effects of denosumab vs alendronate on bone mineral density (BMD), bone turnover markers (BTM), and safety in women previously treated with alendronate. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23(suppl 1):S473. Abstract M395 and poster.

-

Cummings SR, McClung MR, Christiansen C, et al. A phase III study of the effects of denosumab on vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fracture in women with osteoporosis: Results from the FREEDOM trial. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23(suppl 1):S80. Abstract 1286 and oral presentation.

Cette présentation a été appuyée par une subvention éducationnelle sans restrictions accordée par Amgen Canada.