Geriatrics: An Unintended Journey

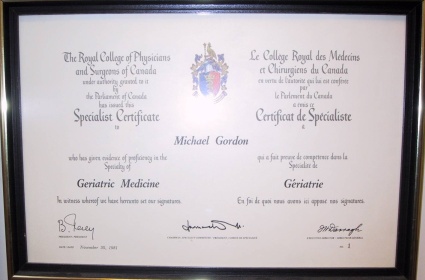

I looked at the certificate that came as registered mail in early December 1981. I already knew that I had passed the first Geriatric Medicine Royal College examination, with the oral taking place in Winnipeg, which when compared to Toronto was bitterly cold. I recall thinking as the examiner asked me questions that he was asking me more of an internal medicine examination than a geriatric medicine oral, but I wasn’t going to quibble with him as the encounter seemed to be going well. By the end of the day I knew I had been successful but the contents of the envelope held a surprise. In the right-hand corner of the certificate was the number one. I had received the first Canadian certificate of specialization in Geriatric Medicine which I knew was not because I was the first successful candidate but because my name must have been the first in the series of those who passed. But that number one has held a symbolic place in my life and career from the day I received that elongated piece of paper with the Royal College coat of arms in its middle.

Certificate #1 of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

The journey started about 38 years earlier when I as a young boy moved from Dearborn Michigan to Brighton Beach in Brooklyn to live with my maternal grandmother. She was divorced and living alone a few blocks from the actual finely sanded Brighton Beach on the Atlantic Ocean. The apartment had only one large bedroom which I shared with her and my younger sister. My parents slept in the living room which was divided by a low-set bookcase into the sleeping area and guest area. In the guest area besides a sofa and a few large chairs was a Sohmer baby grand piano, which had been purchased by my grandmother for my mother during the depression years, being paid for by a weekly payment plan on which they never defaulted. Therefore this gorgeous piano was mine to learn on a few years later and now sits in the home of my eldest daughter who carries on the tradition of ownership.

“Tell me again about why you came to America and what was it like when you came.” That was a recurrent question I asked my grandmother, affectionately called by the Yiddish “bubby”, especially when the lights were out in the room before we went to sleep. She would recount the stories from Eishyshok , the small shtetl in Lithuania where which was her home prior to her immigration to the United States. I heard about her village and her family and then the pogrom which left many people injured and killed which precipitated the decision by her family to go to America where they already had some distant relatives.

Eishyshok in its glory

I heard about the terrible ship voyage and how so many people died because of the awful primitive conditions. She told me about living in the immigrant Jewish neighborhood on the lower East Side of Manhattan and how she got into the garment industry as a seamstress, work that was very common amongst young female immigrants. I heard from her the tragedy of the Triangle Factory fire of 1911 in which 146 of the 500 employees, mostly recent Italian and European Jewish immigrants had died, many brutal deaths from the flames and smoke or from leaping from the upper floors of the factory.

The event propelled my grandmother like others of her background and experience to become members of the Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU), which I heard about from her and their meetings as I grew up. I did not realize until many years after her death, while cleaning up my parents’ house after my mother’s death, that my bubby had in fact completed high school in New York, at night, a feat that was quite remarkable in those days for a woman with her background.

My bubby had a beautiful voice and sang in a Yiddish Choir and often attended performances of the Yiddish theatre to which she took me when I was old enough to accompany her and appreciate what were often massive productions of song and dance. One of my tasks as my mastery of the piano became sufficient was to accompany her on the piano when she practiced for recitals. With my mother often out of the house working, my bubby was very critical to my childhood development and I loved being with her, whether it was watching her prepare gefilte fish for Friday night, chopping the fish with a hand chopper in a large oval wooden bowl or bringing her the forvitz (the Yiddish paper Forward) which she read from front to back. I recall once asking her how it was that she spoke what seemed to me so many languages and she said with a short laugh, “Where I grew up, you didn’t know from day to day who was in charge, so in order to survive you spoke all the languages you might need to get by.”

My bubby died when I was 12 years old after an illness the first evidence of which I witnessed on the way back from a Yiddish Theatre production to which she took me. It was a glorious event. On the subway platform of Brighton Beach she suddenly said she did not feel well, staggered a bit and then threw up. After a few minutes of this, she said she felt better and we got home by bus. That was the beginning of the evidence of what apparently were brain metastases from what I think was breast cancer, only because I once saw her coming out of the bathtub and even with my imperfect understanding of female anatomy I recognized that one of her breasts was missing and there was a scar in its place. Her death left a serious lonely void in my life which of course passed with time, but she was always present in my consciousness.

I loved to take things apart, put them back together and figure out how they worked. My father was an engineer and he was a whiz at fixing things. I cannot recall ever having a tradesperson in the house to repair a sink, a roof or an electric appliance. I loved the sciences and math in school and decided I would be an engineer like my father. I even went to one of New York’s special schools within the public system that catered to students with special interests and talents, Brooklyn Technical High School, geared for those interested in careers in engineering. I loved the school, especially the various “shops” which were done after the regular curriculum – woodworking, foundry, sheet metal and best of all machine shop- where one learned to use very complex and sophisticated lathes and punches and drills. Throughout my life I have used the skills learned at “Tech” as we called it, to build and fix the same things my father did during my childhood.

Brooklyn Technical High School

I was so focused on engineering that when it came time to apply to university; the schools I looked at all had special reputations in engineering or were of the high quality technical universities such as the so-called Polytechnic Institutes. Although I excelled in the sciences and mathematics in high school I enjoyed other studies and activities, especially English literature, photography and music. I had developed the habit of reading as a child when one of the weekly activities my father exposed me and my sister to was a trip on Saturday morning to the public library where as we left he always said, “The library is the greatest institution in the world” to which when we knowingly asked, “why daddy?” he would answer with, “because it contains all the knowledge of the world.”

In my last year of high school, while in the process of preparing for and applying to university, I picked up the book that changed my life, The Citadel by the physician-author, Archibald Joseph Cronin(his nom de plum being A.J. Cronin). The book so enthralled stimulated and consumed me that by the time I finished it I decided that I might change my studies from engineering to medicine. I recall visiting the home of a very dear friend-girl to differentiate her from someone with whom I had a romantic relationship, although I actually had hoped to develop one at some point. I mentioned to her that I was thinking of medicine instead of engineering, to which she replied with words that became in many ways the essential step in my decision-making process, “You’d be a much better doctor than engineer. I think you should do it.” That statement was the sum total of my career counseling.

When I broke the news to my parents, my mother’s initial reply was, “It will take so many years,” but I could see from the look on her and my father’s face that they were pleased with my decision. I therefore changed all my university applications to read “pre- medicine” in the field of interest and career goals. For reasons of finance I ended up going to our Brooklyn College, one of New York’s five schools of higher education that later on would coalesce into the City University of New York. I was a chemistry major within the “pre-med” program but managed to focus heavily on arts subjects whenever I had the option and in those days it was required to do a whole range of the so-called 101 courses in English, Philosophy, History, Classics, Social Studies and languages- to which I added a few extra English literature and Philosophy courses which looking back were among the most important educational exposures in my life and which formed the basis in many ways of my future academic and creative interests.

Brooklyn College

One of the profound influences on my education and life was Professor Edgar Z. Friedenberg whose seminal workComing of Age in America, had a profound impact on education in America. He was my Professor in my first 101 Social Studies course and indirectly stimulated me to want to travel in Europe, which at that time (the late 1950’s) was not yet in vogue and certainly not something readily accomplished by people in my socio-economic situation. My parents, being the very unusual and progressive people that they were agreed to my taking six months off from Brooklyn College as long as part of the plan was for “educational” purposes which was accomplished by attending a summer language program in Lausanne Switzerland.

That six month journey changed my life and attitudes towards education and adventure. The last part of the journey which was spent in Copenhagen, much of it in the company of a group of primarily female medical students helped formulate my determination to study medicine on the other side of the Atlantic rather than in the United States which would have been part of the “normal” chain of events. The experience overseas also exposed me to a whole new world of “other” than what were the traditional values and cultural mores and practices of America. I broke the news of my idea of studying overseas to my parents and couched the reasoning into financial terms which was one of the factors that allowed them to agree to consider the proposition. As a reflection of their progressive view of the world, the agreement stipulated a tentative agreement to include having my then 16 year old sister visit me during my fist summer to travel in Europe with me.

My original plan to study in Denmark or other Scandinavian country fell through but I was very fortunate in being accepted to the University of St. Andrews, Scotland’s first university and the third oldest in the English speaking world, founded in 1413 with the medical school being founded in 1450 somewhat after Oxford and before Cambridge in England. I was very fortunate to have been accepted a year earlier than initially anticipated and into second year because of my pre-medical education at Brooklyn College because as I only found out after my first year when my class-mates felt comfortable telling me, one of their classmates died in first year, leaving an empty place in second year. That vacant place went to me so from the tragedy of one young medical school student’s premature death, my future opened up- a bitter-sweet tale when told to me by a few of my closest class-mates.

Medical School in Dundee, Geddes Quadrangle

Medical school in Dundee where the medical was actually situated was wonderful. Once I accommodated to the dreary gray weather, the strong at times unintelligible Dundee accent, the paucity of any food worth eating other than fish and chips and the damp cold of the housing, I had a fabulous experience. The main point of my studying abroad was to travel and indeed with almost five months off a year and a system where medical students could choose places to go and get foreign experience based on place, area of study and time I managed over the years to travel and work in Scandinavia, various Eastern and Western European countries, different places in the United Kingdom, and what became another seminal experience in my life, Israel.

I was exposed to geriatric medicine as a medical student where the Geriatric rotation and ward proved to be one of my favorites because of the instructors and wonderful experience with the “old wifies” as the elderly Scottish ladies were called. One of the geriatric wards in Maryfield Hospital was made of a large room with a potbelly stove at its centre and in the evening all those women patients who could sat around in their easy chairs, drinking tea, chatting and knitting- it was a glorious warm vision and experience as they just loved us young medical students.

Following a student placement in obstetrics and gynecology in Haifa Israel I unexpectedly won the prize in Obstetrics and Gynecology in my final year based on my final examination. The 500 pound sterling prize allowed me to return to Haifa for a 5 month internship on the same ob/gyn service which ended just prior to the 1967 six-day war. I had already fallen in love with the country as a student, but this prolonged period confirmed my initial impression.

Serving as an Israeli Air Force base doctor

I returned to the United States for my U.S. internship at the height of the Vietnam War and chose to move north to Canada following which I immigrated to Israel with my then Israel wife who I had met just prior to the six-day war. I did a six month pathology training rotation when I first came to Israel because of lack of language skills and then unexpectedly was invited and accepted a commission as a physician in the Israel Air Force where I served as an Air Force based doctor which included a monthly rotation as a helicopter evacuation crew member which was among the most exciting experiences I ever had.

On my release from the Air Force I took a position as a senior and then chief medical resident at the Shaare Zedek (Gates of Righteousness). It was during this two year residency that I became involved for the first time since medical school with geriatrics- Shaare Zedek had one of the first dedicated geriatric units in Israel. It was a remarkable experience and I witnessed outcomes that I had not seen on our general medical wards and the idea of a true multidisciplinary approach was taking shape. I also found much humour and good feeling among the staff and patients on the unit as we endeavored to improve the function and quality of life of older patients who had in many ways been dismissed as “not likely to improve” from other medical and surgical sources- this of course changed as our reputation in the hospital and in the city grew.

Israeli Air Force helicopters

I returned to Canada in 1973 with the goal initially of studying nuclear medicine with the plan to return to Israel and help develop that specialty at Shaare Zedek Hospital. Two things happened to change that plan the first being that I realized after a very short time that nuclear medicine did not satisfy my clinical and human interests- although I could master the technical aspects of the profession I missed the deep interactions with patients as people. I therefore decided to transfer back into Internal Medicine. The next major issue was the recognition that my marriage was beginning to unravel and going back to Israel was not going to happen in the near future or at all.

While trying to figure out what aspect of internal medicine or one of its specialties I would pursue I remembered my meeting in Jerusalem with Dr. Abe Rapoport from the Toronto Western Hospital who when being driven back to his hotel by me after presenting as a visiting professor at Hadassah Hospital offered to meet with me if I ever needed his help or advice. I went to him and after explaining what I wanted to do and how much I loved general internal medicine he asked me, “Have you thought of geriatrics?” to which I responded, “I did not know it was a recognized specialty in Canada.” He replied, “No it isn’t but there is a great institution called Baycrest and if you take the position offered to you by Dr. Berris at Mount Sinai as chief medical resident, I am sure he would let you do some work with or for Baycrest which is closely allied with Mt. Sinai.”

Baycrest Hospital for Seniors

I followed his advice and met the staff at Baycrest. I was impressed. I took the position at Mt. Sinai and started doing consultation for Baycrest for applicants and for those seniors transferred to Mt. Sinai for treatment. Within two weeks I knew that I had found my place in Medicine. The rest is history: working to get Royal College Certification which came in 1981, helping to build the capacity and reputation of Baycrest, returning to study Ethics and receiving my Master’s degree in 2001 and having a most satisfying career in academic geriatrics and ethics at Baycrest, Mt. Sinai and the University of Toronto- an unintended but most wonderful journey.

Dr. Michael Gordon is currently medical program director of Palliative Care at Baycrest, co-director of their ethics program and a professor of Medicine at the University of Toronto. He is a prolific writer with his latest book Moments that Matter: Cases in Ethical Eldercare followed shortly on his memoir: Brooklyn Beginnings-A Geriatrician’s Odyssey. For more information log on to www.drmichaelgordon.com