Elsa Marziali, PhD, Professor and Schipper Chair, Gerontological Social Work Research, University of Toronto and Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care, Toronto, ON.

An internet-based psychotherapeutic support group for family caregivers of persons with dementia was developed in a series of pilot studies and evaluated in a feasibility study with 34 participants. A user-friendly website was developed that included video conferencing in two formats: group and one-on-one. Following 10 professionally facilitated sessions, each group evolved into a web-based self-help support group. Six-month follow-up interviews showed overall positive participant responses with regard to learning to use computers, negotiating the website, providing mutual guidance and support, and improving management of caregiver burden and stress.

Key words: internet, caregiver, support groups.

Introduction

Family caregivers, largely women, provide the health and social care for dependent family members who have long-term chronic illnesses. Family caregiving can span many years depending on the stage of illness progression and the family’s resources for managing the needs of the care recipient. Caregiver stress and negative health outcomes are common. Intervention programs for family caregivers typically focus on a) support and/or educational groups; b) individual psychotherapy; c) interventions focused on the care recipient such as respite care; or d) combinations of two or more of these approaches. Most models of intervention produce small-to-moderate improvements in caregiver stress, depressive mood, subjective well-being, and coping ability.1-3 Intervention programs are delivered face-to-face in either group or individual formats and are either clinic based or provided in the home of the caregiver or care recipient. Providing similar services using technology such as the Internet presents significant challenges.

E-Health Programs for Family Caregivers

Technology has been used in the past to enhance intervention strategies with family caregivers of persons with dementia. ComputerLink is an Internet-based support network including a public bulletin board, private e-mail, and a text-based question-and-answer forum facilitated by nurses.4,5 The participants benefit in the short term but participation lags in the long term. REACH (Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health),6 a comprehensive multisite research program, evaluated the benefits of interventions designed to enhance family caregiving for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. In addition to face-to-face support services, two of six participating sites used digital telephone systems to enhance the delivery of information and consultation to caregivers. The Internet was not used for service delivery in any of the REACH programs. Overall, the intervention programs showed benefits to caregivers in terms of reduced stress and higher skill acquisition.

Virtual Support Groups

Our intervention program for dementia caregivers was developed through a series of pilot studies and subsequently evaluated in a feasibility study implemented in two remote areas: Timmins, Ontario and Lethbridge, Alberta. For the pilot studies, three groups of six spousal caregivers agreed to participate with informed signed consent. The groups were facilitated by two experienced social workers, initially in face-to-face format and subsequently via Internet-based video conferencing. The overall aim of the intervention was to decrease the amount of stress experienced by the caregivers as well as enhance their knowledge and skills in managing the care of the dependent relative. The professional facilitators provided the intervention online for 10 sessions, and continual feedback was solicited from the participants regarding both the technical and clinical aspects of the program.

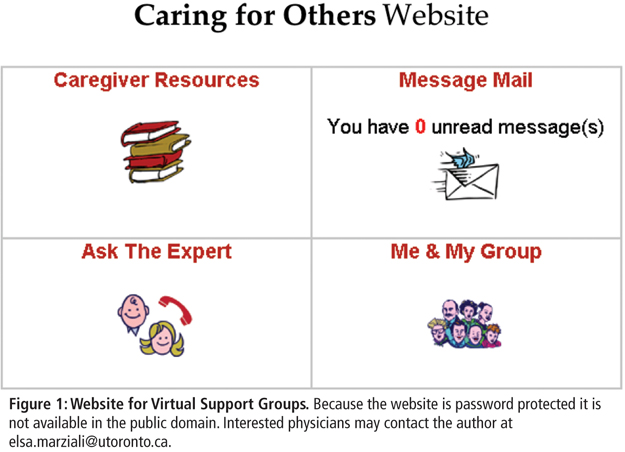

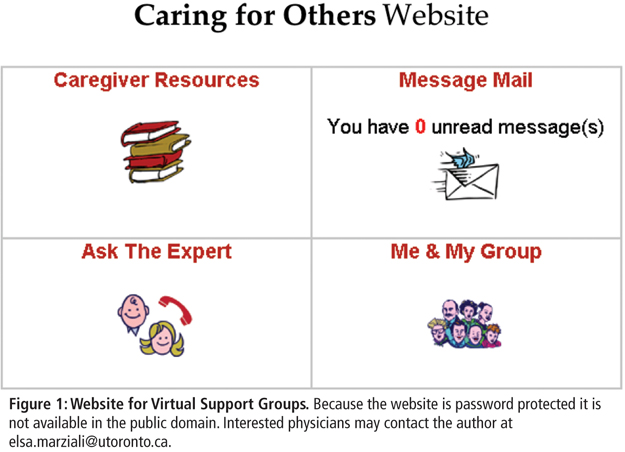

The pilot studies yielded several modules. The first was an easy-to-use, password-protected website with links to a) online disease-specific information handbooks and self care strategies for the caregiver; b) e-mail; c) a question-and-answer forum; and d) video conferencing for one-on-one communication or virtual group interactions. Secondly, we used an intervention training manual that included a theoretical framework and strategies for facilitating an online virtual group. Next, a computer training manual presented a simplified way of understanding the basic steps for using computer hardware and software (Figure 1).

These program modules were used to implement the feasibility study. In all, 34 caregiver-care recipient dyads were recruited (17 at each site with five to six caregivers of persons in each of three disease groups--Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and stroke). With informed, signed consent the caregivers agreed to baseline and follow-up interviews as well as having the video conferencing sessions archived for subsequent analyses. Technicians at each site installed computer equipment and software in the homes of all participants and used the computer training manual to train the users. A clinician at each site was trained to facilitate the groups according to the intervention training manual. Subsequent to the 10 facilitated sessions, in each group a member assumed the facilitator role and the groups continued to meet weekly for an additional period of three months. Research assistants interviewed the caregiver participants in their homes prior to participating in the online group intervention and six months later.

Caregivers’ Responses At six month follow up, over 90% of the caregivers reported benefiting from their participation in the virtual support group either “extremely” or “very” positively. They formed strong, mutually supportive bonds within the group and acquired new knowledge and psychosocial support that enhanced their caregiving role functions. All reported a decrease in levels of stress associated with caregiving and several reported that their participation in the group supported a decision to delay admission of their family member to institutional care.

When asked about their experiences using the website for communication, 78% indicated that it was very easy to use. When asked what they liked most about the website, some of the caregivers responded “that it was accessible,” and appreciated the opportunity to “have visual contact with other group members.”

Conclusions Overall, the project results demonstrated that an online, video conferencing based intervention program for caregivers is feasible. The older caregivers with no prior experience with computers readily learned to manage both the hardware and software. This program is replicable because of the emphasis placed on careful development and evaluation of both the clinical intervention and the “Caring for Others” website through which it was delivered.

This project was supported by grants from CANARIE, Canada, Bell Canada University Laboratories at the University of Toronto, Canada, and the Katz Centre for Gerontological Social Work, Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care. Renee Climans and Arlene Consky, social workers at the centre, provided clinical expertise throughout the implementation of the project.

References

- Bourgeois MS, Schulz R, Burgio LD. Interventions for caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a review and analysis of content, process, and outcomes. Int J Aging Hum Dev 1996;43:35-92.

- Sörenson S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventionswith caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist 2002;42:356-72.

- Schulz R, O’Brien A, Czaja S, et al. Dementia caregiver research: in search of clinical significance. Gerontologist 2002;42:589-602.

- Brennan P, Moore S, Smyth K. The effects of a special computer network on caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Nursing Research 1995;44:166-72.

- Payton FC, Brennan PF. How a community health information network is really used. Communications of the ACM 1999;42:85-9.

- Schulz R, Burgio L, Burns R, et al. Resources for enhancing Alzheimer’s caregiver health (REACH): overview, site-specific outcomes, and future directions. Geronologist 2003;43:514-31.