Click here to view the entire report from the 28th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Canadian Geriatrics Society

Getting Started in an Academic Career: An Interactive Workshop

Speaker: Kenneth Rockwood MD, FRCPC, FRCP, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS.

Addressing his audience as both a clinician and as an academician, Dr. Kenneth Rockwood suggested that the best synonym for research is any effort within academic medicine that serves to “make patient care better.”

The Commitment to Academic Medicine and Research

Dr. Rockwood sought to convey the professional commitment academic medicine requires. He advised that the time and energy that aspiring academicians must commit, in addition to that required for clinical work, is significant. Nonetheless, the opportunities to make a difference in patient care in this arena are significant, and geriatric medicine as a specialty is in growing demand. Compensation levels are increasingly aligning with other specialties after a history of ranking behind.

Dr. Rockwood reminded listeners that within the academic community there are research and teaching tracks, and opportunities for those interested in administrative work. For those hoping to teach, he suggested that instruction in geriatric medicine must continue to result in coherence in the body of the teachings, and that they must contribute to the effort to clarify the guiding principles behind the knowledge conveyed.

The Distinction of Geriatrics: The Comprehensive Approach

To illustrate, Dr. Rockwood discussed the core skill underpinning the specialty. Dr. Rockwood described geriatricians as having to be “masters of complexity.” In practice, this can translate as having to think about several items simultaneously. Geriatric medicine is distinguished, according to Dr. Rockwood, not only by its comprehensiveness and complexity (accounting for factors such as the patient’s functional course, future quality of life, the result of the mental exam, preventive medicine, and more) but also by a domain of action very unique to this subspecialty.

Geriatric medicine is foremost a subspeciality of internal medicine concerned with older frail people who have complex problems, Dr. Rockwood stated. Geriatricians are distinguishable from internists by their embracing of the complexity of the patient’s total health picture. In contrast, the instinct of other specialties is to itemize problems and address them individually. The Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment that embraces complexity due to frailty is the signature of geriatric medicine.

This leads to particular challenges and rewards, explained Dr. Rockwood. In academic medicine, they must work to change people’s minds and behaviours—that is, empower those they collaborate with to understand what the problems are. Further, the comprehensive nature of the practice of geriatrics requires multidisciplinary teamwork. Conflicts between disciplines and problems of coordinating the knowledge of multiple professionals can sometimes compromise meeting the goal of better care.

Knowledge Translation in Geriatrics

Dr. Rockwood advised aspiring academicians to not only teach subjects they are passionate about but to convey coherent teachings and principles that are able to change practices. This is the work of knowledge translation: mediating concepts in a way aimed at helping others. Geriatricians who teach and research must offer not only a coherent body of knowledge, but offer instruction in clinical tools that match what he called the operative realities in practice. He also stressed that teaching must be responsive and its aims changed according to the audience’s needs.

Again addressing the complexity marking geriatric medicine as both a clinical and academic specialty, he noted that geriatricians are not the only professionals dealing in complex situations of grave consequence. The airline industry, for example, is noted for developing procedures and analytic tools that aid life-and-death decision making in complex situations. Geriatric medicine might learn from some of the modes of thinking, analysis, and action that they have adopted.

Regarding the development and use of frailty as a concept and the evolving frailty scales, he urged that clinicians embrace the complexity working with frail older adults presents, but also foster their capacity to discern patterns. Dr. Rockwood noted the preponderant use of informal clinical signs used to corroborate worsening frailty, and asked listeners to offer their own deductive shorthands (e.g., a patient’s incapacity to move off his/her pressure points). He recommended that listeners attend to the difficulties associated with typical versus atypical presentations among older patients, noting that one area where geriatrics must improve is in remaining open to patient pleas of not being well. Geriatrics teaching must work on advancing practitioners’ comprehensible skill sets, he suggested.

Obtaining Advanced Training in Geriatrics

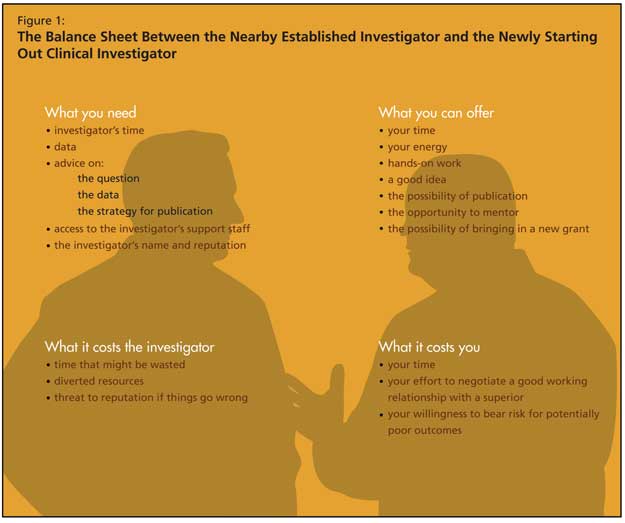

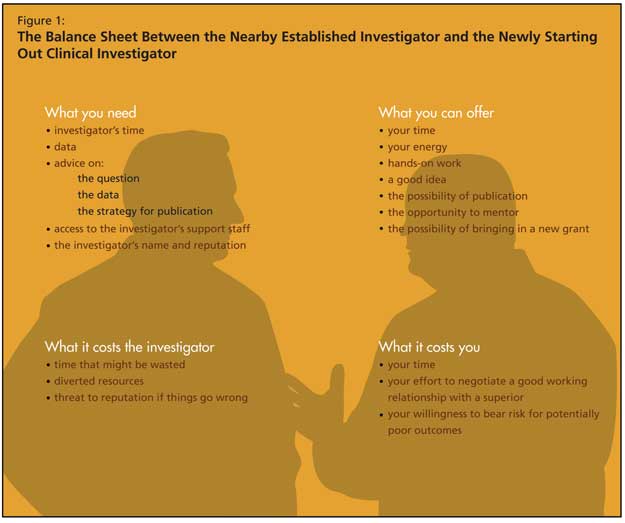

Dr. Rockwood offered concrete tips on obtaining advanced training in geriatric medicine. He strongly recommended aligning with a mentor, and he offered several tips on founding and furthering such relationships (e.g., familiarizing oneself with the mentor’s work, offering research assistance). The value to the student is not only a gain in knowledge but access to the mentor’s data as well as the mentor’s name and collaboration for publications. In exchange, the student offers his/her time, energy, enthusiasm, ideas, and the chance to bring longevity to the mentor’s work (Figure 1). Other specific tips Dr. Rockwood offered to aspiring academicians and researchers included not too narrowly limiting options by tying all of one’s research to a particular technology or treatment technique, and ensuring that one’s work contributes to a body of research and clinical data being fortified on a daily, incremental basis.

In the question forum, Dr. Rockwood reiterated that research should embody one’s values as a health professional. He noted that there is opportunity for nonacademic physicians to do work often associated with formal academics and researchers. Dr. Rockwood observed that such working relationships are usually fostered through collaboration with formal academicians, who are often open to this kind of engagement. Dr. Rockwood also offered observations on working with representatives from the pharmaceutical industry. He advocated that anyone doing this kind of work recall that it is a clear business proposition from the industry’s standpoint. Valuable information can emerge from work supported by industry, Dr. Rockwood suggested. The advantage of such involvements are often the networking opportunities with other physicians and groups that a clinician might not normally come into contact with.

What trainees thinking about entering into academia most require, Dr. Rockwood stated, are time, money, and help. Time spent doing clinical work is the foremost requirement for clinical research. This is where the trainee establishes both his/her bona fides as well as builds essential professional relationships. Further, the aspiring researcher needs funds for acquiring and supporting a good research assistant and research grants. Finally, the work requires the help of others: namely, access to established investigators who may serve as allies.