If one is in medical practice long enough it sometimes seems like that sense one gets when sitting in a waiting room and picking up a years old copy of Time® magazine and not realize that it is years out of date, as many of the stories seem to be the same or very familiar. I have a 30 year old tuxedo which fortunately comes in and out of vogue cyclically which allows me ( as long as appropriate size accommodating alterations have occurred) to keep wearing it without my feeling that I am “out of fashion”.

The challenges that face all practitioners and family members who care for those living with dementia are myriad. Cognitive impairment and behavioural issues top the list of concerns expressed by families, with the second layer being impairment of activities of daily living which requires assistances in many basic domains. Over the years the approaches to care especially for those with the range of behavioural issues which might range from withdrawn apathy to agitated aggression and disruption of other people’s function and privacy. The latter often becomes a problem in congregate living situations and may lead to crises when the facility expresses concerns about the ability to continue care of others’ lives are negatively affected.

In this question for methodologies to decrease these negative or as recently renamed “reactive” behaviours, the typical “medical” approach has generally been pharmacological. This has spawned a whole drug-based industry including regulatory attempts to modify and curtail the use of such medications because of evidence-based negative consequences of the medications which are often additional to the risk of the underlying disease itself. Psychologists, social workers, recreational and music therapists have all added over the years various modalities of interventions with the hope that they might individually or in combination might more safely decrease the degree of behavioural problems without compromising the person’s function, dignity and quality of life.

With this in mind it was refreshing to see recent references to programs in which “doll therapy” was being utilized as a modality to address some of the behavioural manifestations of those living with dementia living in long-term care facilities. The article that brought the program to mind was recently published in the Feb. 3, 2014 web-based article from Nursing Ethics where the focus of the article was on the ethical implications of the intervention more that the efficacy and clinical impact of the use of dolls in BPSD and other manifestations of those living with dementia.

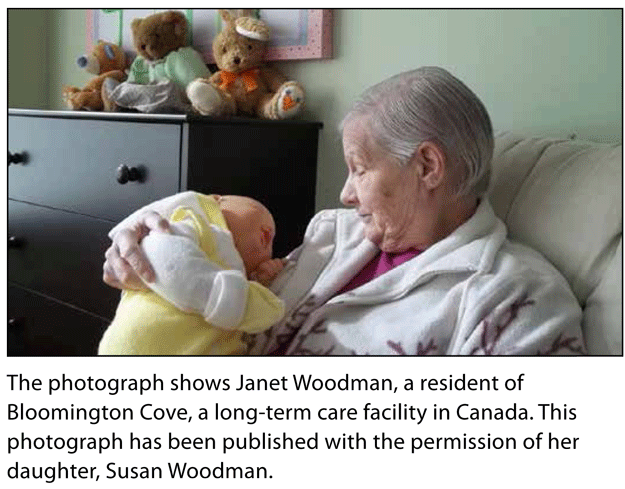

One of the long-term care facilities to which I provide ethics workshops for the staff that cares exclusively for those living with dementia has had a doll therapy program for many years. At Bloomington Cove LTC facility, the range of doll-based interventions includes individual provision of dolls as well as programs in which groups of residents take part in various forms of care-provision and nurturing activities to the dolls which are of a soft and “cuddly” characteristic. The director of the facility believes strongly that the doll-based intervention brings out the natural and at times vivid desire and latent abilities and wish of almost exclusively female residents to express affection, physical nurturing and emotional attachment that clearly is stored in the repository of their brains and personalities which when tapped release positive feelings and actions which can replace the often disruptive reactive states that BPSD often elicits.

The ethics focus on this intervention which is not new is encapsulated in the Nursing Ethics article which says, “The use of doll therapy for people with dementia has been emerging in recent years. Providing a doll to someone with dementia has been associated with a number of benefits which include a reduction in episodes of distress, an increase in general well-being, improved dietary intake and higher levels of engagement with others. It could be argued that doll therapy fulfils the concepts of beneficence (facilitates the promotion of well-being) and respect for autonomy (the person with dementia can exercise their right to engage with dolls if they wish). However, some may believe that doll therapy is inappropriate when applied to the concepts of dignity (people with dementia are encouraged to interact with dolls) and non-maleficence (potential distress this therapy could cause for family members). The article continues with, “This article suggests that by applying a ‘rights-based approach’, healthcare professionals might be better empowered to resolve any ethical tensions they may have when using doll therapy for people with dementia. In this perspective, the internationally agreed upon principles of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities provide a legal framework that considers the person with dementia as a ‘rights holder’ and places them at the centre of any ethical dilemma. In addition, those with responsibility towards caring for people with dementia have their capacity built to respect, protect and fulfil dementia patient’s rights and needs.”

In contrast to the ethics focus approach to doll-based therapy another article, published by Carefect, focuses primarily on the beneficence (benefits) impact of such intervention as follows, “Doll therapy provides many benefits for Alzheimer’s patients that engage in it. One of the most important benefits of doll therapy is that it provides Alzheimer’s patients with social interaction and allows them to have the chance to care for someone again instead of just being the person that is being taken care of. Many seniors are calmed by their doll and it can often create a distraction for them from upsetting events. Having a baby doll often reminds Alzheimer’s patients of fond memories of when they were a new parent which can have a very positive effect on them. Many seniors will enjoy rocking their baby doll which can also help them fall asleep if they have trouble sleeping themselves. Family caregivers looking for activities for their loved one can try purchasing baby doll clothes or even actual baby clothes for their loved one to put on the doll. Many of the lifelike dolls are big enough to fit in newborn clothing, so family caregivers can purchase a few outfits for their loved ones to put on their doll. Family caregivers can even consider buying a stroller for the doll so that their loved one can push it around the house and get some exercise while playing with their doll. Many seniors enjoy singing to their doll, so family caregivers can join in or encourage their loved ones to sing on a regular basis. The most important thing though is to make sure that all family members are educated on doll therapy. Many people may find it odd to see their elderly loved one playing with a doll, especially if they were not educated on the way doll therapy works and the benefits of such therapy for people suffering from Alzheimer’s or dementia.”

What does this mean for those responsible for providing as much as possible sensitive, client-focused, beneficent and the least harmful interventions possible that will allow those living with dementia to experience the least conflict and anguish in their emotional experiences? This should be while promoting as much as possible some semblance of quality of life and emotional connectivity with their world, however distorted or limited as it might be because of their cognitively impaired state. Although as in all aspects of medical and other health care interventions the ethical implications cannot and should not be ignored, we in the healthcare professions must be careful to make sure that our approach is sufficiently balanced with the focus always on the well-being or those we care for and the realization that in a complex world of caring for those with dementia, there may always be some question remaining in the realm of ethics, but these must not supersede the real daily beneficial impact that may accrue to those we collectively care for. Doll Therapy as well as the wide array of alternative therapeutic interventions should be high on our list of considerations as we struggle to make the life of those we care for whose scope of enjoyment and social participation may be limited by their disordered brain functioning.

This blog was originally published at: http://www.annalsoflongtermcare.com.