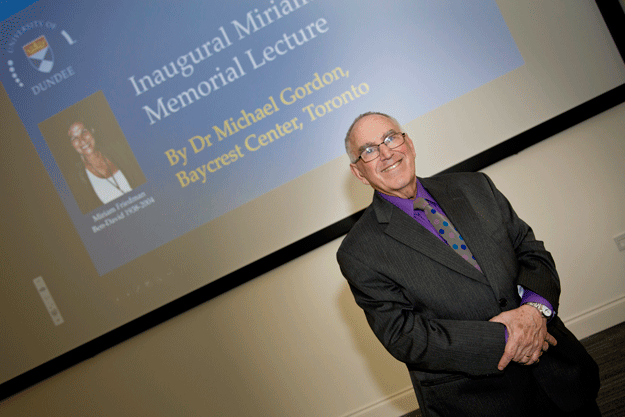

I was the honoured speaker for this lecture series endowed in the Name of Miriam Friedman ben-David, a well-known medical educator who had close ties to the University of Dundee which is my medical school alma mater, although when I graduated it was still part of the renowned University of St. Andrews.

When I graduated from medical school in 1966, geriatrics was already one of the medical subspecialties in Scotland and I recall how much I enjoyed my rotation through the geriatric unit. The instructors were marvelous and at a time of open so-called Nightingale wards, in the evenings it was common for a whole ward’s worth of older women to be sitting in a circle, knitting and drinking tea about a pot-bellied stove in the middle. Think what a fire marshal would say about that these days! It was very homey and the staff were very attentive to these patients, some of whom as would be the case today suffered from some degree of Alzheimer’s disease. In those days the term was not really used yet and if a woman had problems with forgetfulness and other cognitive features of dementia, the doctor or nurse would often say, “Ach, it’s all right, she’s just a wee bit dotty.”

I visit Dundee on a period basis for reunions and for professional exchanges. It is lovely to share experiences with geriatrics in Scotland vis a vis what we have in Ontario as a reflection of Canada. Scotland, as part of the British National Health Service (NHS), has of course a publicly funded universal health care service—in fact it was the first, the pioneer of universal health care systems that became in many ways the model for many others especially in Commonwealth countries—with Canada’s taking some points from the NHS.

Like all health care systems, it has many positive points and some negative points and like most systems it has its proponents and its detractors. Also like systems everywhere including Ontario, and Baycrest as one of its prime geriatric centres, most of the deliberations and complaints by providers and consumers are related to the shortage of funds to do everything that might be necessary to provide for quality care for elders living in the community and those in long-term and acute care facilities.

But as a system of aged care (as they often call it rather than geriatric care)—the comprehensive nature of the system, even if always somewhat short of optimal funding, is one of its special features. Many of the components of geriatric community care that are not covered in Ontario, such as rehabilitation services, are all under the NHS umbrella of funding in Scotland. Doctors in general are on salary so that the issue of fee structures is not much of an issue as they are occasionally (as right now in Ontario); however there are salary disputes from time to time, but medical strikes are not possible as they are not possible here.

On this visit I did not get much of a chance to tour in any detail any of the geriatric facilities, but did get a chance to talk to members of the geriatric and palliative care faculty at the University of Dundee who also served in the NHS.As in the past, I was taken with their passion and devotion for those they care for. My visit on this occasion was very short and part of it, beyond my lecture on end-of-life dementia care, was speaking to two nurses doing geriatric research projects. I also had the opportunity to do a workshop with 10 very enthusiastic medical students doing a geriatric rotation on the origins of what is called Evidence Based Medicine (EBM) which in many ways had its developmental genesis in McMaster University in Hamilton—a close neighbor and geriatric academic colleague of ours.

The visit was terrific with special social aspects including a celebratory dinner after my lecture in what is called the “Principle’s House”—a beautiful site with many marvelous paintings of well-known Scottish artists of the last two centuries. But the culinary highlight actually occurred a few days earlier while I was visiting one of my classmates and his family who are quite dear to me—we went out and rather than a “take-out” had a sit-down traditional, classical, sumptuous fish and chip dinner with an extra order of “what pudding” which is also a traditional Scottish deep friend dish consisting of meat and fat, bread and oatmeal formed into a large sausage—indescribable and something that brought back many culinary memories of my almost six years in Scotland, first as a medical student and then as an intern.

The lecture was a very much appreciated honor to me on top of this glorious recollection of all the years and many stories I recall from Scotland and the homage I pay to not just my training and teachers but to the wonderful care that they provide to their elderly citizens.

This blog was originally posted on the Baycrest staff blog.

Dr. Michael Gordon is currently medical program director of Palliative Care at Baycrest, co-director of their ethics program and a professor of Medicine at the University of Toronto. He is a prolific writer with his latest book Late-Stage Dementia: Promoting Comfort, Compassion, and Care and previous two books being Moments that Matter: Cases in Ethical Eldercare followed shortly on his memoir: Brooklyn Beginnings-A Geriatrician’s Odyssey. For more information log on to www.drmichaelgordon.com