I am reading the biography of a well-known author. Like other biographies, one of the wonderful aspects of such writing is appreciating those people who have had a profound influence on the life of the person whose biography is being read. We all know about the usual influences from family members, teachers, friends, colleagues and sometimes people whose influence was one of those haphazard accidents of circumstance and nature. Sometimes it might be a book or lecture, movie, poem or piece of music that has had such an impact on a person’s life that they attribute who they are, in least in part of that particular person or event.

I can identify a small number of people, events or books that had such a profound influence on my life and I sometimes wonder what would have happened had those influences not occurred. Of course I had a number of teachers in primary and secondary school that were inspirational and supportive of my inquisitive nature as well as some who were quite suppressive of my interests that were somehow outside the formal structure of the school system. One example of a suppressive spirit was an English teacher I had in junior high school who after reviewing the books proposed for in-depth book reports as a special project literally “forbad” me from reading Thomas Wolfe’s classic Look Homeward Angel which I had in fact already read, but because of her dictum was not able to use it for the book report—her motivation was her self-internalized Catholic beliefs and the negative view of such a book by the Catholic Church—such a prohibition would not be acceptable currently, but at that time had a profound influence on me as she told me the book was “evil” when I had found it inspiring—both components of the event influenced my views of the Church which had not been particularly positive as a young Jewish boy knowledgeable of the history of the Church in Jewish history, the events of the Inquisition, and most recently the Holocaust. Wolfe remained one of my favourite authors throughout the rest of my developmental years. The official Catholic prohibition against the reading of certain books was reversed by an official Papal decree published on the 15 June 1966.

The negative influence of certain teachers, books and events which often had the opposite effect of the intended or expected was more than balanced by those individuals, books and events that helped nurture those aspects of my personality and value systems that ultimately were instrumental in my ultimate choice of profession and my deeply ingrained value systems which were incorporated into my personality inclinations.

It was in my first year at Brooklyn College, that I entered in 1958 after graduating from the exceptional Brooklyn Technical High School which set the stage for my life-long interest in science, engineering and the desire and ability to “fix things” a character trait supported by my father’s engineering profession and his personal capabilities as a perpetual “fixer” of all things that had a mechanical source of function. The two first year college teachers were quite different, but their influence was similarly profound. I had entered college as a pre-medical student which was a decisive change in my original post-high school goal that was to apply for a degree in engineering, in the footsteps of my father. This decision was changed by a book I read during my last year of high school which profoundly changed my educational directive and in essence the course of my adult life.

I do not recall the reason I chose to read The Citadel by A.J. Cronin. I was an avid reader, but why this particular book caught my attention is no longer part of my recollective capacity. It may very well have been one of those events that “just happened”, the book was there and it looked interesting. The result was dramatic. I suddenly thought about studying medicine rather than engineering which had been my direction. Soon after I read the book I visited a dear friend, a girl about whom I had romantic fantasies, but who looked to me as a close friend which in the absence of the alternative coming to pass I cherished. I mentioned to her my musings about medicine and she said with great certainty and passion, “You would make a much better doctor that engineer—do it”. I left her house and within about 10 minutes I pondered her statement as I arrived home where I informed my parents about my decision (which during that 10 minute walk had been finally determined). I could see that my father was pleased, but he was not a very verbally expressive person. My mother said, “Oh it is such a long time of study”, but I got the sense that she was pleased as well. At this point there were no doctors in my extended family although other than my mother all of my immediate elders despite coming from immigrant uneducated parents had finished at least undergraduate university degrees. So this would be a new venture for my extended family that ultimately produced a number of physicians—including a very close first cousin and a number of second cousins.

The decision on my part to study in Scotland was the result of spending six months traveling around Europe during my junior year at Brooklyn College, an undertaking stimulated by one of my first professors in social sciences in my first year required course. Edgar Z. Friedenberg, who beyond mesmerizing me in his classes and stimulating me to want to travel, engaged me on my return from my sojourn through Europe that eventually completely changed the direction of my life and studies, as a research assistant for one of his seminal books, the Vanishing Adolescent published a year after I left for medical school. He had such a profound influence on my thinking and the range of my intellectual interests that I felt honoured that he kept in touch with me, even arranging a couple of trips with him to overseas destinations while I was studying medicine in Dundee Scotland. He left the United States and immigrated to Canada to teach at Dalhousie University. His move to Canada mirrored a similar move I made in 1968 also for the same reason—in opposition to the Vietnam War, not as a pacifist, but because I felt the war was a terrible mistake of United States policy.

In medical school in Dundee had a number of mentors that influenced my views of medicine and my approach to the concepts of the “story” of medicine and during my post-graduate years my views of the relationship between the humanities and medicine. The renowned Sir Ian Hill, our professor of medicine taught the art of the lecture that enchants, elevates and deeply engrosses an audience into the mysteries, meanderings and miracles of medicine. His description of the famous Zermatt typhoid fever outbreak of 1963, the year after I started medical school, will never be forgotten and still acts as a model for me for the wonders of the sleuthing required of public health challenges. It was Professor William Walker, our head of Midwifery (Obstetrics and Gynecology in North American parlance) who during my final oral examination asked me why I had a Scottish family name that allowed me to weave my family’s genealogy tale to the point of using up all of my time short of one quick obstetrical question and that resulted in the 500 pound prize. That windfall ultimately financed my trip to Israel that resulted in my connecting to the country in a way that had an impact on my life as almost nothing else has in my adult years.

It was another William Walker who went from the Department of Medicine in Dundee to Aberdeen who I followed there for my first house job (internship) who had the profound influence on my appreciation that one could combine a love for the humanities and medicine. While in Dundee he gave a series of after-hours lectures on “Humanism” which had a profound effect on my world view, already having been primed by my previous exposure during undergraduate education and range of reading. I was so impressed with him that in the culture and practice of post-graduate training in Scotland in those days I deliberately requested on a personal basis that he take me on in the department he was to head in Aberdeen, which he did, and that turned out to be one of the best clinical experiences of my career.

It was the five months following my Aberdeen house job that had the most profound effect on the trajectory of my life. With the 500 pound prize that followed my midwifery examination, I received permission to use it to fund a second “house job” in midwifery in Haifa Israel, a place I had visited as a medical student two years previously. It was during that student visit that I had an epiphany in terms of my identity. Although I was raised in a Jewish family, mostly of secular Jewish persuasion other than my paternal grandparents, I had not a particular interest in that identity other than from the strong historical and cultural ties that I felt. I had a strong sense of the importance of the Holocaust on the history of my people, but Israel itself held no particular powerful attraction to me as it did for many other people with my background. However, in response to many questions from family members why I did not visit Israel while already being on the “other side” of the Atlantic I decided to combine one of my summer medical training experiences to include Greece for a month with a follow-up month in Israel which was “just across the Mediterranean.”

I had arranged to work at the Rambam Hospital in Haifa, named after the great ancient Jewish medical scholar and sage also known by his more complete name (Moses ben-Maimon, or more commonly Maimonides).

The profound experience I had occured on the second day after settling into my small prefabricated hut that acted as housing for interns, residents and visiting students like me. I went to the beach that was adjacent to the hospital which sat on the Mediterranean shore and as I looked around at the throngs of people, many with small children, somewhat reminiscent of my exposure to Brighton Beach where I was raised, I had a sudden wave of recognition. I thought to myself, even though these people were strangers, “these are my people”, every single one of them. When I went on the local service bus the next day I had the same revelation. I kept looking at the different faces, clearly from different parts of the world, light skinned like myself, Slavic looking women with high cheek bones, but fair eyes, dark skinned men with almost black eyes, all speaking what I knew must be Hebrew despite my limited exposure to that language during my upbringing other than what I learned mostly by rote for my Bar Mitzvah. I kept thinking, “I share a history with all of these people”.

I started working the next day and met the head of the department among other members of the staff. Professor Aharon Peretz welcomed me warmly, asked about my heritage and established that he and my grandparents came from Lithuania which I could see meant a lot to him. He asked me what I wanted to learn and when I said “anything and everything” he said I could shadow him in all his clinics as well as other members of staff and if I wanted to assist him in the operating room that too would be fine. I could not believe my good fortune as being in the operating room at that point in my studies was still an exciting option which I did not have that much access to at medical school. I did not realize that the interns on the service would be more than happy to have someone else stand during surgeries and hold retractors which for me was still very exciting as the professor explained everything that he was doing and pointed out all the anatomic landmarks that I had seen only on my anatomy cadaver.

I learned a lot during that month and was given a great deal of latitude in what I could do. I observed Professor Peretz interview patients with various gynecological problems who had been holocaust survivors and were applying for reparations. I noted that whatever the condition which he was very good at explaining to the patient in Hebrew or Yiddish or Russian or it seemed whatever language was necessary, he then explained to me and then signed the necessary reparations form which I learned went to an adjudication committee in Germany which decided on the merits of the claim. When I naively asked if all the conditions were Holocaust related, he paused for a moment, looked at me deeply, drew in a breath and said in perfect English, “As far as I am concerned, every gynecologic problem that afflicts these women either directly came from the holocaust experience or was exacerbated or complicated by that experience. I could see from the look on his face that he felt this was a mission of his to make some sort of amends for what these women had experienced during their years as prisoners, refugees, people in hiding or just experiencing the cold, hunger and monumental trauma and grief related to those dark years of their lives. I only found out later that he was one of the key witnesses during the Eichmann trial in Israel in 1961-62. During a recent visit to a special exhibit at Yad Vashem (the Holocaust Museum) in Jerusalem I saw a picture of him bearing witness at the Eichmann trial, and seeing him there brought back a flood of memories of my time with him in Haifa.

When I left to return to Scotland, I recall the great sense of a new chapter of my life opening up that I did not realize was there. On my return to Dundee I had not formulated a definite plan of return, but knew that in one way or another I would be back to the country I had discovered resonated in my inner-most consciousness. After I received the prize in midwifery and confirmed with my professor that I could use the 500 pounds for a repeat visit to Israel to do in essence part of my internship in obstetrics and gynecology, my plan began to solidify. I would do my first 6 months of post-graduate training as a house-officer under the supervision of Dr. Walker the internist-humanist who had moved to Aberdeen where he agreed to take me on, and then I would return to Israel, a visit I looked to with great anticipation.

Dr. Walker in Aberdeen had a profound effect on my approach to medicine, but also to all the people with whom he came into contact. It was from his modeling and style that I realized the importance of acknowledging and asking the opinion of nurses with whom we were doing rounds, a practice that I integrated into my style of practice after witnessing its positive impact on the staff during that six month period. He deferred at times to the opinion of the head nurse and always sought the input and opinions of the house officers with whom he did rounds, sometimes writing in the chart that a certain idea or suggestion came from one of us—something I had never witnessed before from a staff physician. He could be critical in a very instructive way, but when he praised me for something I did he gave me such a lift and that too became part of my practice-style when I entered into the role of a medical teacher and mentor.

As I came closer to my career choice I had the various influences of rotations, specialties and probably most important the mentors in my life. As it turned out when I ended up settling in Toronto, rather than pursuing a career in nuclear medicine which I had come for, but soon found that the lack of patient contact made it not particularly attractive for me. It was then the influence of two wonderful physicians in Toronto that pointed me in the direction of geriatrics: the first was Dr. Abe Rapoport, an internist and kidney specialist that I had met and gave a lift to in Jerusalem just prior to my move to Toronto, ostensibly to learn nuclear medicine and bring it back to Israel where it had not yet been developed in any substantive way. While driving him back from Hadassah Hospital where he had given a seminar that I attended to the centre of Jerusalem I mentioned that I was going to spend a couple of years in Toronto. He said, “If I can help you when you are there, please feel free to contact me.”

After a number of months doing nuclear medicine it became clear to me that it was not a specialty suited to my medical interests and personality, I did seek out the advice of Dr. Rapoport. After I told him about myself he suggested I look into Geriatrics and contact the people at Baycrest while at the same time pursuing a chief residency position that I became aware or at Mt. Sinai Hospital. When he mentioned geriatrics as something that might satisfy my desire to continue in a broad based specialty in internal medicine and not focus on just one organ system or realm of diseases (such a specialty in infectious disease might provide) I conjured up recollections of the wonderful geriatric unit in Dundee where among other things the staff physicians were among the best in the medical school and the patients were delightful—often referred to with endearment as auld wifies.

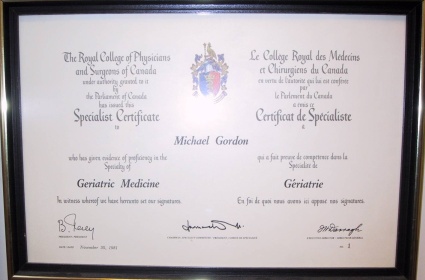

I followed up with a visit to Baycrest and when I was offered the position of chief resident at Mt. Sinai Hospital with which Baycrest was affiliated I requested of my second wonderful mentor, Dr. Barney Berris, the head of the department with whom I would be working if I could do the Baycrest consultations who were at Mt. Sinai while I was working for him. He agreed and besides being a mentor in terms of gentleness, clinical brilliance, and warmth he helped me formulate my career in geriatrics which when I passed my Royal College examinations that fall, resulted in him and another mentor, Dr. Henry Himel, the chief of medicine at Baycrest offering me a conjoint position which I accepted—thus determining my career path.

For many years my roles and path of academic development moved in a very satisfying direction with areas of great satisfaction in many domains especially in teaching and writing. I had always had an interest in writing, but with my academic roles the opportunities grew and I was able to undertake initially academic articles and then in 1981 my first book was published, Old Enough to Feel Better: A Medical Guide for Seniors. With it a new aspect of my career was launched that of author and over the years since that time a number of other books in addition to articles for the professional and lay press where the objects of my writing interests, all of which reflected my experiences in medicine and the care of the elderly.

As the various challenges of geriatric medicine began to coalesce in my practice I became increasing interested in the ethical aspects of eldercare which resulted in my completing a masters in ethics which was soon followed by an interest and the incorporation into my clinical and administrative practice palliative and end-life care—with all these threads of these special interests intersecting in a very meaningful way.

This eventually resulted in the focus of my clinical care, ethical deliberations, writings and teaching to become increasingly focused on dementia, especially the later stages where special aspects of care and caring come into play and where ethical conundrums become very common. The culmination of these influences has been my most recent book, Late Stage Dementia: Combining Compassion, Comfort and Care. The result has been a dramatic shift in my approach to my clinical ambulatory practice and focus on my teaching of trainees who accompany me in the clinic and my role helping those in our palliative care unit understand the special challenges of caring for those with non-malignant disease especially those with dementia, an increasing challenge in the long-term care system.

I have been very fortunate along the path of my career to have had many teachers and mentors who have inspired, guided and influenced me on the path that finally became my own and now gives me the opportunity to do the same for my students and medical trainees. It goes back to one of the tenets of the teaching of medicine, that one has the duty to learn and then the duty to teach so that the continuity of the wonderful art and science of medicine is assured for the future.

Dr. Michael Gordon is currently medical program director of Palliative Care at Baycrest, co-director of their ethics program and a professor of Medicine at the University of Toronto. He is a prolific writer with his latest book Late-Stage Dementia: Promoting Comfort, Compassion, and Care and previous two books being Moments that Matter: Cases in Ethical Eldercare followed shortly on his memoir: Brooklyn Beginnings-A Geriatrician’s Odyssey. For more information log on to www.drmichaelgordon.com

A National Post story (Nov. 8) reported that New Brunswick was the latest province to move in the direction of offering patients more choices about end-of life-care, beyond the standard “do or do not resuscitate” policies.

A National Post story (Nov. 8) reported that New Brunswick was the latest province to move in the direction of offering patients more choices about end-of life-care, beyond the standard “do or do not resuscitate” policies.