The Role of RANK/RANKL/OPG Pathway in Bone Loss: New Insights

Targeting RANK Ligand Increases Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women: Results from Phase 3 Trials

Speaker: Alexandra Papaioannou, MD, MSc, FRCPC, Professor, Department of Medicine Director, Division of Geriatric Medicine, McMaster University, Geriatrician, Hamilton Health Sciences Centre, Hamilton, ON.

Dr. Alexandra Papaioannou reviewed the results of Phase 3 trials of denosumab, which she described “an exciting new compound” under investigation. As Dr. Robert Josse had explained, denosumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody (IgG2) that binds with high affinity and specificity to human RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B) ligand (RANKL). RANKL is an essential mediator of osteoclast activity.1-3 Dr. Papaioannou noted that no neutralizing antibodies have been detected in clinical trials to date,1,3 and that the effects of denosumab on bone resorption appear reversible.3

Denosumab, which reduces bone turnover markers, is delivered via subcutaneous injection every 6 months, an advantage in an older patient population. It has a mean half-life of ~25–46 days.4

Dr. Papaioannou reviewed four Phase 3 studies of denosumab in post-menopausal osteopenia and/or osteoporosis.

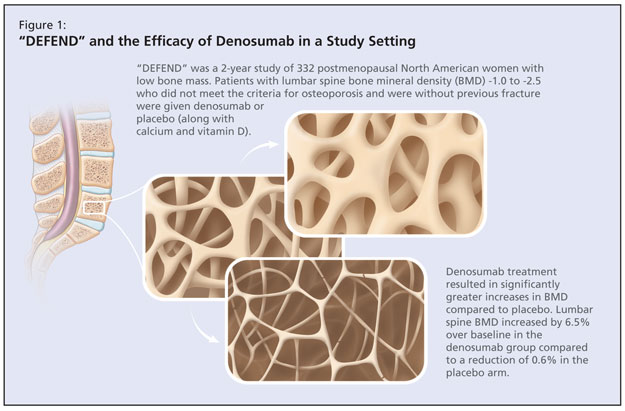

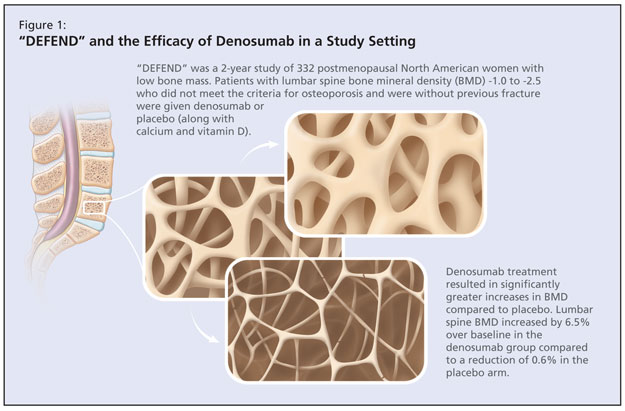

The DEFEND study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that aimed to determine whether denosumab treatment could prevent lumbar spine bone loss in menopausal women with osteopenia (Figure 1).4 This 2-year study of 332 postmenopausal North American women with low bone mass investigated denosumab or placebo in patients with lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) -1.0 to -2.5 who did not meet the criteria for osteoporosis and were without previous fracture. Mean age was 58 years, which Dr. Papaioannou noted to be a younger population. The baseline mean lumbar spine BMD T-score of participants was -1.61. Participants were randomized to either 60 mg denosumab or placebo for 2 years. All patients received ≥1,000 mg of calcium and ≥400 IU vitamin D daily. The primary endpoint was percent change in lumbar spine BMD at 24 months. According to published results, denosumab treatment resulted in significantly greater increases in BMD at all measured sites compared to placebo (P < 0.05; 95% confidence interval [CI]). Lumbar spine BMD increased by 6.5% over baseline in the denosumab group compared to a reduction of 0.6% in the placebo arm. Adverse events occurred in both arms, the most commonly reported of which were arthralgia, nasopharyngitis, and back pain. There was a slight trend in the denosumab arm for serious adverse events.

The DECIDE study was a randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study that evaluated the effect of denosumab compared to alendronate on percent change in BMD in the total hip at 12 months in 1,189 postmenopausal women.5 This was a noninferiority study of postmenopausal (≥ 12 months) women with low bone mass and a T-score ≤ –2.0 at lumbar spine or total hip. Participants were a mean age of 64 years; ~24% had previously used medical therapy for osteoporosis and up to 50% had prior fracture. Patients were randomized to denosumab injections (60 mg every 6 months) plus oral placebo weekly or oral alendronate weekly (70 mg) plus subcutaneous placebo injections every 6 months. The primary endpoint was change in BMD at total hip after 1 year. According to the published results, denosumab treatment resulted in significantly greater increases in the percent change from baseline in BMD at all skeletal sites measured compared with alendronate. Statistically significant increases in BMD at the total hip were observed for the denosumab group compared with those treated with alendronate (3.5% vs 2.5%; P < 0.0001). Dropout rates were similar in both arms, and the incidence and type of adverse and serious adverse events were balanced.

Dr. Papaioannou next detailed the STAND study, a randomized, double-blind, active-controlled Phase 3 study of women previously treated with alendronate.6 She described this study as having particular utility given the common scenario of patients on a regime of alendronate who seek to switch treatment. The study evaluated the effects of transitioning to denosumab on changes in BMD and biochemical markers of bone turnover, and on safety and tolerability compared with continuation of alendronate therapy. Participants were postmenopausal women (mean age 68 years) with low BMD previously treated with alendronate 70 mg once weekly or equivalent for ≥6 months. Their BMD measurements corresponded to a T-score ≤ –2.0 and ≥ –4.0 at the total hip. Patients were randomized to denosumab injections (60 mg every 6 months) or oral alendronate weekly (70 mg). The primary endpoint was the percent change from baseline in total hip BMD at 12 months. The authors reported that BMD at the total hip increased by 1.90% from baseline at month 12 in subjects transitioning to denosumab compared with a 1.05% increase from baseline in subjects continuing on alendronate therapy (P < 0.0001). Adverse events, serious adverse events of infections, and neoplasms were balanced between treatment groups.

Finally, Dr. Papaioannou detailed the FREEDOM study, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study aiming to determine whether denosumab treatment reduces the number of postmenopausal women with incident new vertebral fracture.7 The ongoing study includes 7868 postmenopausal women (-4.0 < BMD T-score < -2.5) 60-90 years of age and excludes individuals with severe or more than two fractures. Patients are randomized to denosumab injections (60 mg every 6 months) or placebo. Primary endpoints include the incidence of new vertebral fractures as well as the safety and tolerability profile of denosumab.

References

-

Bekker PJ, Holloway DL, Rasmussen AS, et al. A single-dose placebo-controlled study of AMG 162, a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANKL, in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 2004;19:1059–1066.

-

Elliott R, Kostenuik P, Chen C, et al. Denosumab is a selective inhibitor of human receptor activator of NF-Kb ligand (RANKL) that blocks osteoclast formation and function. Osteoporos Int 2007;18:S54. Abstract P149.

-

McClung MR, et al. Denosumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. New Engl J Med 2006;354:821–31.

-

Bone HG, Bolognese MA, Yuen CK, et al. Effects of denosumab on bone mineral density and bone turnover in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:2149–57.

-

Brown JP, Prince RL, Deal C, et al. Comparison of the effect of denosumab and alendronate on BMD and biochemical markers of bone turnover in postmenopausal women with low bone mass: a randomized, blinded, phase 3 trial. J Bone Miner Res 2009;24:153–61.

-

Kendler DL, Benhamou CL, Brown JP et al. Effects of denosumab vs alendronate on bone mineral density (BMD), bone turnover markers (BTM), and safety in women previously treated with alendronate. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23(suppl 1):S473. Abstract M395 and poster.

-

Cummings SR, McClung MR, Christiansen C, et al. A phase III study of the effects of denosumab on vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fracture in women with osteoporosis: Results from the FREEDOM trial. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23(suppl 1):S80. Abstract 1286 and oral presentation.

Sponsored by an unrestricted educational grant from Amgen Canada Inc.