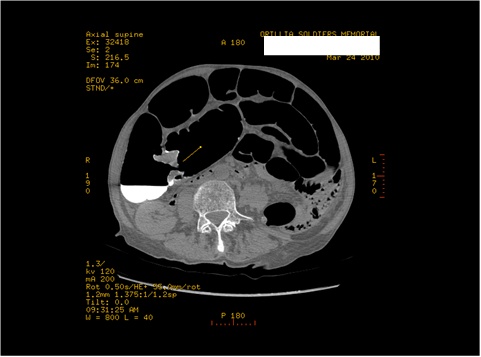

The closest I came to Egypt was the Sinai Peninsula which was under Israeli control following the Six-Day War before it reverted back in 1979 to Egypt’s jurisdiction under the Sadat-Begin accord stewarded by then President Carter. From 1970-71, during my service in the Israel Air Force as a physician, I would rotate for duty at Rephidim Air Base which was the Hebrew re-name of Bir Gifgafa, which was the Egyptian name for the isolated air strip 90 km east of the Suez Canal. It would be my home for three days every month to make sure our advance station pilots had round the clock medical access. They literally sat in their Mirage interceptors for hours on end. I and the other doctors were there to care for them and the crews that serviced their planes. The mosquitoes at night were terrible and I recall looking at the blood speckled wall, where I had successfully swatted my nemesis. No matter how often the screens were repaired they always managed to enter my Spartan room, my nose and ears and every part of my skin even though I slept, despite the heat, covered from head to toe by blankets.

From Rephidim we performed helicopter evacuations all along the Bar Lev line. This was the first line of defense on the Suez Canal. We also covered the armor and infantry bases spread around the Sinai as part of the defense against Egypt with whom during the period of my service, the War of Attrition: in essence an air, artillery and missile war took place. Sometimes a mission required the helicopter evacuation crew to move closer to the Canal Zone if we were in a situation in which forces might cross the Canal and might need to be evacuated from enemy territory.

Serving as an Israeli Air Force base doctor

I recall one such mission where our base for over-night readiness was a Hawk anti-aircraft missile encampment. I watched mesmerized: the battery of Hawk missiles rotated rapidly and whiningly every time an Egyptian plane took off from beyond the Canal and headed towards Israel even for only a few moments before it veered in a different direction. I had a vivid nightmare of having crossed the Canal to extricate a soldier and being pursued by Egyptian soldiers to whom I was trying to explain that I was a doctor from Brooklyn and would not be much of a prisoner pleading my case while brandishing my Beretta side arm which I had learned to use months earlier during my officer’s training course. When I awoke in the morning, having slept fully clothed in my khaki multi-zippered flight suit, the sun was rising, the Hawks were quiet and the helicopter captain was giving orders to my medics and paratrooper crew to pack our things as we were “going home” (“ha beita”) -- a phrase I mastered early in my quest to learn Hebrew, literally “on the job” during my air force service.

During my last six weeks of military service, by then as a reservist, after having completed my regular military duties and just prior to my leaving Israel for post-graduate training in Montreal, our helicopter got a call to evacuate a Bedouin boy with measles and severe dehydration from the Sinai Peninsula in the region of Santa Katarina. This was the site of an ancient monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai where according to the Old Testament; Moses received the Ten Commandments from God. With the setting sun swathing the desert with pink and purple hues, the monastery loomed ahead, barely visible in the darkening horizon. As we landed near the spot, illuminated by a few flares lit by a district field nurse, we could see a small make-shift stretcher holding a boy who, when I got close, I could see was covered in a measles rash and was severely dehydrated and delirious with fever. His father looked at me as the nurse explained who we were and I said my “salam aleykim” greeting as the boy was prepared for the flight to Eilat, where we had arranged for his treatment. I managed to get an intravenous into him before loading him into the Bell helicopter knowing how difficult it would be to successfully undertake such a maneuver with the jolting, undulating and bouncing movements, once the helicopter was in flight.

Santa Katarina Monastery with the Sinai range in the background, Egypt

The father followed in after the boy, his eyes wide in wonderment. The flight did not take that long and I felt the comfort of the dripping of the intravenous into the boy’s arm and anticipated that he would be fine once he received enough fluids. This was confirmed the next day when the hospital was contacted for follow-up so I could complete my medical evacuation report.

It would have been nice if my associations with Egypt, which had just recently made the front pages of newspapers, computers and television world wide, as the population successfully revolted against its dictator Hosni Mubarak, could have been more positive. While trying to empathize with those demonstrating in the streets I could not suppress my negative experiences as the air base medical officer who had to bear witness to the Egyptian military treatment of two of the pilots from my air base whom they had captured. As the television news continually showed the mounting political crises, I happened to be reading David Grossman’s latest book To the End of the Land in which one of the main characters recalls his torture and suffering at the hands of his Egyptian captors and another character describes the terror experienced by the soldiers left in the bunkers on the Suez Canal’s Bar Lev Line, having learned that massacres had occurred to their colleagues in bunkers that had been overrun by Egyptian soldiers who had crossed the waterway at other junctures at the beginning of the 1973 Yom Kippur war.

My first actual associations with Egypt related to Israel, occurred during the early summer of 1967 after I had finished a 5 month internship in obstetrics and gynecology at Rambam Hospital in Haifa. This followed a 6 month internship in Aberdeen Scotland which took place after my graduation from my medical school in Dundee Scotland in June 1966. I left Israel in late May 1967 to visit my sister who was a Peace Corps worker in Tunisia. As I left Israel during those late days in May and arrived in Tunisia in early June, the atmosphere in Israel was foreboding as Egypt’s president; Abdul Gamel Nasser amassed his army in the Sinai Peninsula and closed the Straits of Tiran, choking Israeli’s water access to the Red Sea. Within two days of arriving in Hammam Sousse, a small Tunisian village where my sister was developing a pre-school program, the Six-Day War broke out on June 5th. For three days the only radio contact I could get, using a battery powered old short-wave radio, was local Arabic broadcasts which my sister could translate, and an English transmission from Egypt which chronicled the gradual and graphic destruction of Israel. The broadcasts were accompanied by martial music and the most vicious language to describe the country I had just left and the people with whom I felt a very strong bond, whose utter destruction was predicted. Fortunately all that was being broadcast were Egyptian lies and the truth came out to the world a few days into the war with Egypt eventually surrendering a few days later – but the words of the English broadcaster have remained vivid in my memory and those images although erroneous of Tel-Aviv burning from Egyptian victories cannot be erased.

The graphic and emotionally compelling account of the character in Grossman’s book brought back memories of my pilot neighbor on the air base at which I served. He was a Phantom F4 pilot and his co-pilot and navigator/weapons control person was, like all of the airman on the base, one of my patients who in keeping with their love of flying would do anything humanly possible to avoid my grounding them because of, for example, an upper respiratory condition which for them could be very dangerous with the sudden changes in air pressure but which they nevertheless tended to minimize. He was a very handsome and likeable young man with deep blue eyes and fair hair, the kind of person about whom, those who do not understand the Israeli/Jewish mosaic of appearance might say, “He does not look Jewish with his blond hair and blue eyes.”

IAF F4 Phantom

One day on the radio I heard that a Phantom had been shot down and the two crew members had been observed ejecting from the plane and parachuting to land. I was driving at the time and like anyone in my position I felt a pang even without knowing if the crew was from my base but knew that it could be the case as we were one of the bases with Phantom squadrons. When I returned to the base I discovered that not only were they from my base but indeed they were my neighbor and his co-pilot. I was devastated but immediately took on my professional role as the base doctor and visited the pilot’s wife who lived next door. She, like the wives of most pilots, had her way of dealing with this potentially impending tragedy and was receiving, as best she could all the base staff, pilots and their wives who visited to give her moral support – “after all he had parachuted out and there were international rules of war and prisoners”, even though many knew that the practice by Egyptians towards military prisoners was not always what it was supposed to be.

A few days later the news came that the two crew members were both alive but that one was “very severely injured” and the other had a fractured leg. Then weeks of quiet until I received a call at the base medical office that the co-pilot had “died” from his wounds and was being returned to Israel in exchange for some Egyptian prisoners. I heard quietly a few days later that there was evidence that his death had been due to or aggravated by electric shocks to his body. There was no new word about my neighbor.

One early evening while driving back to the base from one of my stints of working on the local kibbutzim or moshavim (communal farms) as a locum, while their doctor was often doing their reserve duty, I heard that my neighbor had been returned to Israel, very ill and was at Tel Hashomer Hospital. I wheeled around and drove to the hospital in Tel Aviv and found that he had gangrene of his broken leg and was in renal failure. As I arrived I heard that he had just been taken to the operating room for an amputation and would be going on to renal dialysis. His prognosis appeared awful and I could hear murmurs from the doctors in the hall about what terrible shape he was in and how awful had been his medical treatment in Egypt. Despite low expectations because of his terrible condition, he survived and eventually after rehabilitation and a refresher course was accepted to medical school-- something he would often talk to me about, during some of our nighttime neighborly chats, calling it a suppressed wish of his.

The last time I saw him was in the parking lot of the Tel Aviv University Medical School where unless you knew him very well you would not know he was walking with a leg prosthesis -- he greeted me warmly and told me how much he was enjoying his medical studies.

A few years ago, while visiting a family member of my wife’s brother who had immigrated to Israel, as we sat on her roof-top patio in Tel-Aviv she started talking about how strange the world could be in terms of where experiences and occurrences take you. She mentioned someone she knew “who had been a pilot, was shot down, almost died and then went to medical school….”- as she continued I sat up in my chair and asked her if she was talking about my neighbor and she looked at me and said, “you know him?” to which I said, “I was his neighbor on the base, of course.” She then told me he in fact had become a very senior physician in the air force and was just finishing his career and was focusing on archeology as a new career path. And the last piece of information was that he lived across the street. He was not home that afternoon when I ventured to his apartment but I told a young lady who said she was his daughter who I was and I wrote a little note. I was leaving the country that night so it was not until a year later that I connected with him.

After a very warm greeting he filled me in on his life and I marveled at how he managed to turn his near tragedy into a great success and was now redirecting his energies away from medicine altogether into another career. We talked about mutual friends from the base and he showed me the picture of the chief of the air force to be who was another neighbor and a star pilot who took me on a most exhilarating flight in an F4 phantom as his gift to me for having completed the first Israeli fight surgeon’s course which they allowed me to take even though my tour of regular duty was coming to an end.

Israeli Air Force days

My recollection of my neighbor who survived his captivity and torture and his co-pilot who did not, kept intruding on my thoughts as I observed in repeated episodes of televised world news, reports of what was happening in Egypt. Would these people, now free from the shackles of a military dictatorship currently at least at “cold peace” with Israel, find a way to resurrect their hostility to the country and join those whose agenda was an existential threat to the country that I love so much. As I presently follow the press reports from Egypt I feel frightened that some of the potential future leaders of the new government are those who have even during the period of the peace treaty, expressed enormous hostility towards Israel.

The confluence of thoughts and personal experiences related to the Egypt of the past made it difficult for me to share in what seemed to be a general optimism in the West about its future. I have become obsessed with the news out of that country hoping for signs that the situation will not regress and become part of a regional threat that appears to gain traction around the world that threatens Israel’s ability to defend itself and its wonderful, inclusive, creative way of life. How Egypt goes in the next little while may presage what Israel will be facing in the years to come. I hope that my personal recollections and associations will be able to be filed away as the “then” as will the literary depictions in Grossman’s book.

As someone who witnessed the sorrows of the war, if there is a return to the past hostility, with the pre-eminence of Egypt in the Middle East, my deep distrust and associations will be justified. Whatever one can hope for as a future should include Egyptian and Israeli populations that have learned from the past and will focus on peace and a desire to build a Middle East in which both Egypt and Israel can have a “warm peace” to replace the cold one that has existed for so many years.

Dr. Michael Gordon is currently medical program director of Palliative Care at Baycrest, co-director of their ethics program and a professor of Medicine at the University of Toronto. He is a prolific writer with his latest book Moments that Matter: Cases in Ethical Eldercare followed shortly on his memoir: Brooklyn Beginnings-A Geriatrician’s Odyssey. For more information log on to www.drmichaelgordon.com