Fragilité : À la recherche d’un paradigme clinique et de recherche approprié

Conférencier : Howard Bergman, M.D., professeur et titulaire de la chaire Dr Joseph Kaufmann et directeur du service de gériatrie, centre de santé universitaire McGill, Montréal (Québec); codirecteur du groupe de recherche Solidage, Montréal (Québec); directeur du réseau québécois de recherche sur le vieillissement et du Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec, Montréal (Québec); président du conseil consultatif, Institut du vieillissement, Instituts de recherche en santé du Canada, Ottawa (Ontario).

Le terme fragilité est fréquemment utilisé par les professionnels de la santé qui s’occupent des personnes âgées, a fait observer le Dr Howard Bergman. Néanmoins, le concept reste mal défini. Qu’est-ce que la fragilité, quels en sont les éléments, et comment l’évaluer en milieu clinique? Ce terme sert-il l’effort pour atténuer l’évolution défavorable de l’état de santé chez les personnes âgées?

Développer le concept de la fragilité et comprendre le processus de vieillissement

Selon le Dr Bergman, l’étude de la fragilité reste un défi puisqu’il n’existe pas de critères bien définis pour la caractériser. La différence entre la fragilité et l’incapacité, et la manière dont les chercheurs et les cliniciens définissent les effets du vieillissement par rapport au marqueur de fragilité, sont des aspects de la connaissance médicale qui continuent à évoluer. Par conséquent, les cliniciens utilisent le concept sans se concerter sur sa signification, et ce problème s’accentue par le fait que la fragilité est un terme non médical du langage courant.

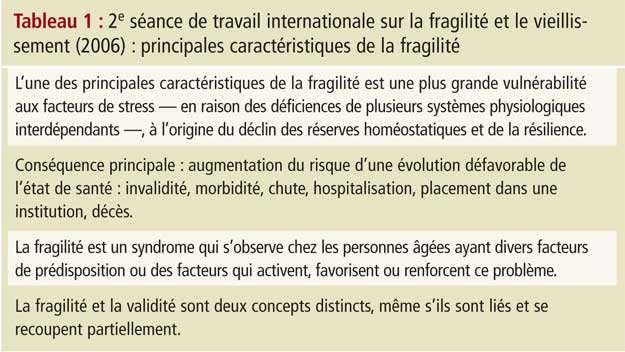

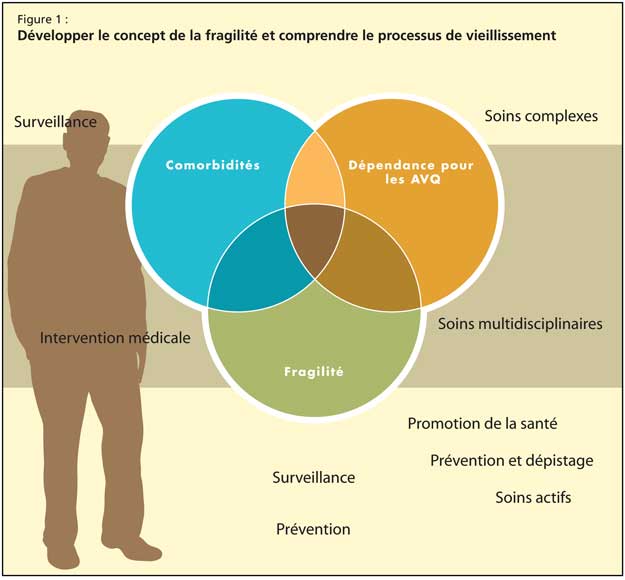

La 2e séance de travail internationale sur la fragilité et le vieillissement, qui s’est tenue à Montréal en mars 2006, a cherché à répondre aux questions clés et aux controverses entourant le concept de fragilité. Cette séance de travail a débouché sur la définition des principales caractéristiques de la fragilité (Tableau 1). Les participants se sont entendus pour dire que la fragilité correspond à une plus grande vulnérabilité aux facteurs de stress, en raison des déficiences de plusieurs systèmes physiologiques interdépendants. Ces déficiences seraient à l’origine du déclin des réserves homéostatiques et de la résilience. Le groupe de travail a admis que la fragilité et l’incapacité sont deux concepts bien distincts, même s’ils se recoupent partiellement (Figure 1). Une des caractéristiques principales de la fragilité est qu’elle est associée à une augmentation du risque de morbidité et de mortalité, a déclaré le Dr Bergman.

On a décrit la fragilité grâce à plusieurs éléments combinés, notamment les anomalies physiologiques, les déficiences des fonctions physique, cognitive ou psychologique, et d’autres caractéristiques, comme l’âge avancé.

Selon le Dr Bergman, les stratégies de recherche qui utilisent l’approche fondée sur le parcours de vie peuvent contribuer de façon considérable à notre compréhension actuelle de la fragilité. Cette approche interactive et personnalisée considère que le processus de vieillissement est le résultat de facteurs survenant tout au long de la vie, comme les expositions environnementales, les prédispositions génétiques et les comportements en matière de santé. Des facteurs essentiels survenant tout au long de la vie pourraient déterminer si une personne vieillit sainement ou non. Une telle approche clinique et de recherche tente d’expliquer l’hétérogénéité du déclin fonctionnel chez les personnes âgées.

Controverses actuelles liées à la définition et à l’utilisation du concept de fragilité

La fragilité n’est pas encore un instrument clinique. Ce concept demeure associé à des controverses et des zones d’ombre : il reste notamment à faire la distinction entre les maladies chroniques et la fragilité. Selon le Dr Bergman, il s’agit d’une relation complexe : même si les maladies chroniques et la fragilité sont parfois associées, la majorité des personnes fragiles souffrent de maladies chroniques, alors que les personnes atteintes de maladies chroniques ne sont pas toutes fragiles; c’est là la différence essentielle. La prévalence de la fragilité augmente distinctement avec le nombre et la gravité des maladies chroniques. On tente cependant toujours de déterminer si la fragilité est un trouble secondaire ou un état sous-jacent. De plus, ce n’est pas la même chose pour une personne d’être fragile ou de présenter un grand nombre de comorbidités. En matière de soins de santé, il est important de considérer les enjeux liés au contexte. Par exemple, des études suggèrent que les patients ayant un accès restreint aux soins de santé seront plus fragiles.

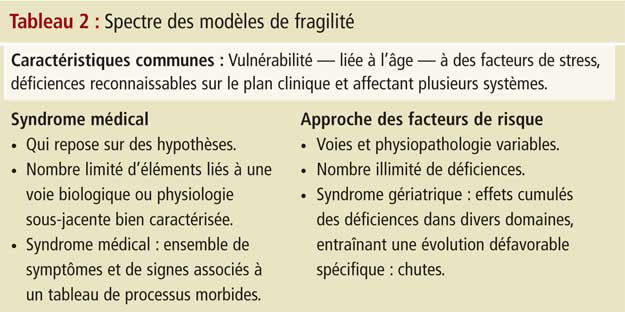

Il existe un spectre de modèles de fragilité. À l’une extrémité du spectre, la fragilité est représentée comme un syndrome médical, tandis qu’à l’autre extrémité il s’agit d’un groupe de facteurs de risque (Tableau 2).

Si l’on considère la fragilité comme un syndrome, avec des caractéristiques de base bien définies, on pourrait tirer d’importantes leçons du syndrome métabolique, a suggéré le Dr Bergman. Comme pour la fragilité, la définition clinique du syndrome métabolique est un sujet de discussion et de controverse. Puisqu’il s’agit de syndromes, on s’attend à ce que la présence d’éléments multiples soit plus fortement corrélée à une évolution défavorable, que la somme de chaque élément.

Le Dr Bergman a reconnu que l’utili-sation accrue du concept de fragilité entraînait des inconvénients. Par exemple, les médecins pourraient surestimer l’ensemble des symptômes, négligeant un symptôme particulier qui pourrait s’avérer précieux. De plus, étant donné que les seuils associés à certaines des mesures de fragilité proposées, comme la vitesse de marche ou la force de préhension, n’ont pas encore été établis, il est difficile de déterminer comment classer les individus. Le fait d’introduire un diagnostic de « fragilité » en pratique clinique peut également s’avérer dangereux, car une appellation impropre peut avoir des conséquences négatives sur la santé mentale d’un patient ou sur la prise de décision en matière de santé.

Selon le Dr Bergman, cependant, le concept de fragilité pourrait s’avérer de grande valeur pour les médecins, puisqu’il est associé à une utilité fonctionnelle en pratique clinique. Le terme identifie un sous-groupe de personnes âgées vulnérables dont le devenir est très susceptible d’être défavorable. En matière de santé, les besoins des personnes âgées indépendantes sur le plan fonctionnel et montrant une fonction cognitive apparemment normale peuvent être négligés si les médecins ne prennent pas en compte les marqueurs reconnaissables de la fragilité.

Selon le Dr Bergman, les marqueurs de la fragilité permettent aux planificateurs de soins de santé d’effectuer des prédictions utiles. À une plus grande échelle, une utilisation clinique de ce concept pourrait améliorer notre compréhension du processus de vieillissement et permettre aux médecins de mieux caractériser l’hétérogénéité de la santé des personnes âgées. En raison du vieillissement de la population, le fait de pouvoir mieux cibler les risques des personnes âgées atteintes d’une maladie chronique, mais non handicapées, et d’y remédier, pourrait entraîner des interventions plus ciblées en matière de santé et, par conséquent, améliorer l’évolution de la santé. Par exemple, le Dr Bergman a cité une étude montrant que des soins aux patients qui retardaient l’apparition d’une invalidité ou d’une dépendance, ne serait-ce que d’un ou deux ans, réduisaient considérablement les besoins en matière de soins de lonque durée et de ressources des établissements.

Conclusions et recommandations

Le Dr Bergman a conclu sa présentation en déclarant que bien que la recherche et le débat sur la fragilité ont permis de mieux comprendre les personnes âgées, le concept reste à l’heure actuelle d’une utilité plus théorique que pratique. En définitive, davantage d’initiatives de recherche sur la fragilité permettront d’en déterminer la pertinence et d’évaluer si les professionnels médicaux réussissent à améliorer la promotion de la santé, la prévention, le traitement, la rééducation et les prestations de soins pour les personnes âgées.