Click here to view the entire report from the 4th Canadian Colloquium on Dementia

Dementia and Depression: The Importance of Recognizing their Relationship

Speaker: Dr. Kristine Yaffe, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Neurology and Epidemiology; Co-director of the Clinical and Translational Sciences Training Program, University of California, San Francisco; San Francisco, CA, USA.

Dr. Kristine Yaffe, of the University of California, San Francisco and San Francisco VA Medical Center, sought to shed light on the co-occurrence of depression and dementia, which are commonly encountered by practitioners caring for aging adults. Cognitive impairment affects up to one-third of older adults. Similarly, depression appears frequently and can co-occur with dementia. Both affect quality of life, and contribute to increased morbidity and mortality among this population segment.

Why, Dr. Yaffe asked, might they go together? Patients presenting with symptoms of major depression often experience altered cognition as an effect of the mood disorder, and, similarly, depressive symptoms can accompany dementia as part of the disease. This is particularly the case in dementia with Lewy Bodies and frontotemporal dementia, but symptoms can appear in the setting of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as well. Depression may not only be a reaction to cognitive problems but a risk factor for later cognitive impairment.

The depressive symptoms that tend to co-occur with deteriorating cognition include deficits in executive functioning and multitask domains, as well as inability to focus or retain new information. Processing speed is affected. However, on testing, memory impairment is often not registered and is not a hallmark of the paired conditions.

Dr. Yaffe stated that this constellation is recognized and tends to be termed pseudodementia. She questioned the value of the term, as the entity is not really “pseudo” and seems to call into question the validity and veracity of the patient’s experience. On the contrary, the symptoms are very real but not necessarily permanent. A careful cognitive evaluation is required; further, cognitive testing should be repeated subsequent to treating the depression.

Rather than thinking in terms of or aiming for clear-cut diagnosis, she encouraged listeners to think of patterns of disease expression. The focus must, however, remain on the particular individual and the uniqueness of his/her case.

Depressive Symptoms in the Setting of Cognitive Impairment

The general constellation Dr. Yaffe suggested that clinicians be aware of is marked by a general slowing down. She noted that typical depressive symptoms can differ in the setting of cognitive impairment; dysphoria, rather than major mood symptoms, is the hallmark. Other symptoms to watch for among older patients include loss of interest in usual activities and decreased social interaction.

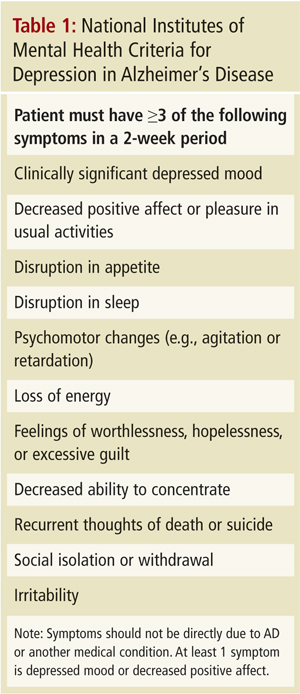

Regarding the validity of currently available testing scales, Dr. Yaffe considered the commonly used dementia scales to be of value in the setting of mild and moderate dementia (Mini-Mental State Exam score ≥15). In advanced dementia, the scales are of diminished utility. Further, she claimed that the commonly used Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) criteria for depression are not very useful in this setting and advocated using the National Institutes of Mental Health Criteria for Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease (NIMH-dAD) criteria (Table 1). These are not dissimilar to DSM-IV but are less stringent—roughly, one major symptom is required, plus two others, for a positive diagnosis. She reminded listeners that the fifth revision of the DSM is forthcoming and new criteria are to be expected. Currently, the NIMH-dAD is a more sensitive scale and a better assessment tool when dealing with co-occurring dementia and depression.

Dr. Yaffe noted that many patients with dementia present with depressive symptoms. It is important to assess for depressive symptoms in dementia as they may bear on both the symptoms of and prognosis for the cognitive state. These patients are at double risk: they are vulnerable to greater functional decline and greater mortality. Neither condition is benign and both are treatable.

Depression may also be a risk factor per se for cognitive decline. Dr. Yaffe advocated watchfulness in the setting of geriatric depression, as patients should be monitored for signs of dementia. In her clinical practice, she will refer depressed older individuals for neuropsychiatric testing as they are at increased risk (by a factor of two to three times) for developing cognitive problems. Research has suggested that in the presence of three to five symptoms of depression, there is a doubling of risk of cognitive decline. This may be due to changes in cortisol; or, it could be an early symptom of neurodegeneration.

It is possible to see structural brain changes in imaging in dementia. Classically, three things appear: one, nothing, in some cases; two, numerous white matter changes, often in the frontal subcortical region, relating to the executive impairment (bringing vascular dementia to the fore); and three, hippocampal atrophy. Given the last, it is unsurprising, she stated, that individuals go on to develop cognitive difficulties. Functional imaging findings often include frontal hypometabolism (in depression), and classic temporal-parietal hypometabolism (in AD).

Treating Depression Co-Occurring with Dementia

As for treatment approaches, when treating geriatric depression in the setting of mild to moderate cognitive impairment, she noted that most pharmacotherapeutic options prescribed for younger adults, such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Figure 1), also work in the older population, with the caveat that one must be vigilant regarding comorbidities and any relevant background medical conditions. Research has suggested that sertraline is of good utility in this patient segment. She noted that the sertraline studies and other relevant studies concerning the co-occurrence of the disorders have found that mood improves but the cognitive deficits tend to remain untouched. In her experience, Dr. Yaffe finds the impairment improves but does not disappear.

As for nonpharmacological treatments, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can be helpful, even in vascular depression. The best strategy involves CBT plus pharmacological therapy. Among aging adults assisted by a caregiver, caregiver education is a key element of the therapy that should aim to redress any misconceptions or negative attitudes about the disorders from which the patient is suffering. Patient support groups are also of high value. While electroconvulsive therapy has been found to have efficacy in the setting of geriatric depression, note that it can cause increased confusion or other altered functioning.

Conclusion

Dr. Yaffe closed with some thoughts about the nature of the relationship between dementia and cognitive deficits. What stems from what, which of the two should be seen as a prodrome, and other key questions lack clear answers. What is clear, she noted, is that these conditions are not benign, they tend to co-occur, and recognizing this is among the key pearls she hoped to impart. Patients need to be followed closely, and their depression needs aggressive treatment.